Relational Critical Discourse Analysis: A Methodology to Challenge Researcher Assumptions

Abstract

This paper introduces a new critical peace methodology—Relational Critical Discourse Analysis. For research to contribute to the well-being of people and their societies, traditional research methodologies need to be examined for biases and contributions to societal harm, and new approaches that contribute to just and equitable cultures need to be developed. As two researchers from dominant, privileged populations, we challenged ourselves to do this by creating and employing Relational Critical Discourse Analysis, a new research methodology that provides space for diverse perspectives and emphasizes the researchers’ interconnectedness with their participants. In this paper we describe the methodology and examine how, within one case study, it increased our ability to (a) listen deeply to participants and (b) be personally impacted by what participants are saying.

Keywords: relational critical discourse analysis, restorative justice, critical peace methodologies, voice-centred relational methods, critical discourse analysis, feminist relational discourse analysis, relational theory

This paper introduces a new critical peace methodology—Relational Critical Discourse Analysis (RCDA). By incorporating restorative justice and relational theories into the established fields of critical discourse analysis (CDA), feminist relational discourse analysis (FRDA), and voice-centred relational methods (VCRM), RCDA was developed to honor the voices of all participants, in particular those with dissenting perspectives, and to involve and uncover how research analysis impacts researcher perspectives. In particular, this paper outlines RCDA methodology and then utilizes a case study to illustrate how RCDA can be used.

The aim of this paper is to describe Relational Critical Discourse Analysis and to present our experience of using this methodology. By offering our experience and sufficiently detailing the impact it had on our research and ourselves as researchers, our intent is to invite interested researchers to engage the methodology, assist in its further development, and thus increase its validity. The question we focus on is: What are the unique offerings of Relational Critical Discourse Analysis for researchers engaged in qualitative critical peace research?

Woven throughout, we describe how Relational Critical Discourse Analysis exposes researcher assumptions, which then can lead to opportunities for researcher transformation that allows for the reporting of more substantial findings and recommendations. RCDA joins the stories of participants with the stories of researchers for a joint counternarration (Gibson, 2020) that moves beyond dominant discourse so that we can “see the world differently” (O’Reilly, 2019, p. 7). Developed and employed in a pre-pandemic time, and re-examined during the Summer 2020 resurgence of civil rights in the US and Canada, this methodology demonstrates its capacity for creating opportunity for privileged academics to deconstruct research and research(er) practices that contribute to the perpetuation of systemic oppression.

*****

We, dorothy and Kristin, wake up uncomfortable these days. It’s been a long time coming. Where once we didn’t give our skin color or European-Canadian heritage a thought, we now hesitate in our personal and professional discussions, in our writing, in our researching, aware that nuances of language can betray default oppressive attitudes, perceptions, and practices that we don’t wish to hold (Wood & Liebenberg, 2019). As such, in our whiteness, we begin to be slightly aware of “the skin we are in” (Cole, 2020), something that the dominant sectors of society that we are a part of have continued to oppressively impose on BIPOC. As researchers, we realize if personal and socio-cultural transformation is to continue, we can’t run from this discomfort, but we need to nurture its growth.

With every protest that surfaces, regardless of cause, those of us who dominate in our communities and countries are challenged to discuss among ourselves what we can give up (McCue, 2020) in order to ensure we are not perpetuating harm for others with whom we share our socio-cultural spaces. This article describes a research methodology we developed and employed to better engage in that crucial discussion and take up the challenge to change.

Relational Critical Discourse Analysis (RCDA) emerged from our common backgrounds in critical theory, restorative justice education, and peace studies. We first used RCDA in a study exploring public perceptions of restorative justice. Rather than using surveys and interviews, we examined the visceral responses of the public who chose to submit negative online written comments in response to online news articles reporting on one significant use of restorative justice approaches—addressing sexual harassment among students enrolled at Dalhousie Dentistry School in 2014.1 We began unaware of how RCDA would impact our understanding of the findings, and also our personal and professional practice moving forward. In the context of our current tumultuous world of pandemic and racial unrest, we examine the potential of RCDA to be a counter-cultural methodology where researchers confront their biases and unconscious, subconscious, or conscious contributions to societal harm in the hope that authentic contributions to the growth of more just and equitable spaces emerge.

Peace methodologies have long taught us the necessity of aligning what we are studying with how we are studying it—that our values need to be present in our processes (Bretherton & Law, 2015; Toews & Zehr, 2003). It is important that those of us interested in peace and social justice education not only aim our research toward peaceful and just ends, but that, as Bretherton and Law (2015) write, we see each stage of the rese arch “as part of a peacebuilding process” (p. 5). In a “post-truth” era, when traditional methodologies seem unable to connect with an increasingly divided people, paying attention to our processes is even more critical. In order to reach across boundaries, at every stage, we need to find compelling ways to inquire into issues and to utilize processes that engage those with whom we may not agree or may have ignored in the past.

For us, Relational Critical Discourse Analysis resulted in a greater ability to (a) listen deeply, and (b) be open to being personally impacted by what participants are saying. As many qualitative research methodologies are strengthened in terms of credibility and depth of analysis through investigator or analyst triangulation (Patton, 2002, p. 560), we found that applying this to RCDA and emphasizing the coresearcher role had significant impact. While there is potential for RCDA to be utilized by a solo researcher, we offer and recommend a co-researcher model to access the exponential benefit of relationship in this methodology. Our experience caused us to conclude that as a methodology, RCDA:

- Has the potential to expose power relationships in the researcher/participant role;

- Allows researchers to be reflexive and alert to their biases and assumptions, thereby increasing opportunities for personal and structural change;

- Deepens understanding of and empathy for the dissenting voice allowing for

- engaged dialogue rather than oppositional dialogue in responding to concerns and research reporting.

Relational Critical Discourse Analysis Methodology Development

Employing Relational Critical Discourse Analysis as a methodology in the case study inquiring into public perceptions of restorative justice resulted in significant findings. However, as important was the impact of being engaged in the methodology as researchers. Utilizing RCDA provided great clarity of our own researcher assumptions of the topic we were studying and of the people involved in our study. Since then, we have both grappled with the findings of our original study and the experience of employing RCDA.

With the Summer 2020 resurgence of civil rights in the US, Canada, and beyond, and the gradual rethinking of a post-pandemic world, it seems an apt time to consider anew how RCDA is a methodology with the capacity for challenging academics to deconstruct research and research(er) practices that contribute to the perpetuation of systemic oppression. As the context of our study did not include marginalized communities of particular origins (i.e., BIPOC), we did not engage directly with concepts such as race and decolonization. However, what we understand as critical theorists is how oppressive perspectives intersect with everything we do and often develop into mainstream researchers co-opting methodologies developed by BIPOC researchers [i.e., critical race theory (Bell, 1995), decolonizing interpretive research (Darder, 2015)]. Having a particular critical methodology that challenges researcher bias and assumptions developed by those of us who are a part of the mainstream, allows us to grapple significantly, to do our own work. As such, one aim of this paper is to present RCDA as a methodology that meets the six critical research characteristics as laid out by Darder (2015), that has shown itself to disrupt our researcher stance and thus has potential for being developed into a methodology of decolonization and anti-oppression from the stance of those of us who traditionally benefit from the lives and work of others. We discuss this fully after we describe how RCDA was developed and used in one particular case.

Methodologies Grounding Relational Critical Discourse Analysis

By introducing Relational Critical Discourse Analysis (RCDA) and classifying it as a new critical peace methodology, we see its potential for adding to the field of decolonizing research. By incorporating restorative justice and relational theories into the methodological approaches of critical discourse analysis (CDA), feminist relational discourse analysis (FRDA), and voice-centred relational methods (VCRM), RCDA was developed to honor the voices of all participants, in particular those with dissenting perspectives that tend to be ignored or silenced within dominant discourse, and to involve and uncover how research analysis impacts researcher perspectives.

In this sense, Relational Critical Discourse Analysis fits snugly with other qualitative approaches to research that rose in popularity, primarily in the 1960s, driven by a desire to “include people historically excluded from social research or included in ways that reinforced stereotypes and justified relations of oppression” (Leavy, 2014, p. 2). Yet, despite socially just intentions, all research methods, crafted and implemented within unjust societies by researchers raised within discourses of supremacy and oppression, hold within them the possibility of perpetuating power imbalances, rather than righting them. Research methodologies are not neutral; as researchers we must continually ask questions about how our research processes and products impact individuals and societies. Thus, with the creation of RCDA, we attempt to add to the methodological approaches that assist with “democratizing science and producing research findings that promote positive changes in society” (Wood & Liebenberg, 2019, p. 1).

Relational Critical Discourse Analysis was created initially for meeting the needs of our case study: to assist in deepening our understanding of public perceptions of restorative justice found in online comments. We did not intend to create a new methodology; our intention was to select an existing methodology most suited to our research pursuit and most aligned with our restorative values. As we engaged with relevant methodologies, we learned from those rich bodies and saw how they might complement one another, but we also identified how restorative and relational theory might add to and strengthen them. It was in the pursuit of an appropriately relational and critical methodology for analyzing online comments that we created Relational Critical Discourse Analysis.

Restorative and Relational Theory

We began with that which grounds our work: restorative and relational theory. Informed by Indigenous worldviews (Pranis et al., 2003; Ross, 1996), relational theory recognizes that “we are broken in relationship; we are also healed through relationship” (Nadjiwan, 2008). Relational theory is both old and relatively recent, drawing on such theorists as Buber, Bakhtin, Dewey, Freire, Gadamer, Gilligan, Heidegger, hooks, Miller, and Noddings (Bingham & Sidorkin, 2004; Llewellyn & Llewellyn, 2015; Schwartz, 2019) to put forward a cohesive frame of reference “based on the assumption that relations have primacy over isolated self” (Bingham & Sidorkin, 2004, p. 2). Jean Baker Miller, who developed Relational Cultural Theory (RCT) in the 1970s, along with other feminist critical theorists, argued that the Western prioritization of self over relationship was a damaging male model of development (Miller & Stiver, 1997). Schwartz (2019) articulates instead the necessity to view relationships as central to human development, since in relationship, “we expand each other’s world” (p. 6).

Restorative justice is fundamentally about the nurturing, sustaining, and repairing of relationships (Hendry, 2009). Vaandering (2015), in her articulation of the critical relational theory that grounds restorative justice, suggests that a restorative justice process is “any relational encounter where the wellbeing and worth of the one(s) I am with, are a priority” (pp. 69–70). Within those encounters, the concern is with the character and conditions of relationships (Llewellyn, 2011). Llewellyn and Llewellyn (2015), viewing a relational theory of justice as foundational to restorative justice, state that restorative processes must be “attentive to the range of private and public relationships that support, or potentially thwart, human flourishing” (Llewellyn & Llewellyn, 2015, p. 24). Restorative justice is much more than simply an alternative approach to dealing with harm; it engages “relational complexity in ways that are required for full and expansive responsivity” to individuals and systems (Llewellyn & Morrison, 2018, p. 346).

Thus, the research methodologies we, as restorative researchers, engage with need to be relational, respectful, responsive, ethical, and in support of human flourishing. One method that can embody these values is listening.

Listening as a Method

Listening is a core process in both relational and restorative theory. In all restorative processes, the act of telling your story and the act of listening deeply to another’s telling are key to transforming relationships (O’Reilly, 2019). Although in our study, we were reading the words of online comments, rather than listening to people’s audible voices, we wanted our approach to embody physical listening as much as possible.

Listening is not inherently a respectful, responsive practice. Dobson (2014), drawing on Waks (2010), identifies three very different modes of listening: compassionate, cataphatic, and apophatic. In compassionate (or active) and cataphatic (or interruptive) listening, two opposite ends of the listening continuum, there is no requirement for the listener to be impacted or moved to action. Dobson (2014) exposes how these two types of listening can actually be forms of oppression: the listener can exercise power in the listening in order to ensure that the status quo is maintained or strengthened. The listener can choose not to listen, to misinterpret, to dismiss or to use information gained through listening to strengthen their own status (Vaandering & Reimer, 2019).

In contrast, apophatic listening is a form of creative, shared power (Crouch, 2013). Apophatic listening requires the listener to remain curious and open, putting aside judgment and assumptions, while attempting to truly hear what is being said. Judgment is suspended in order to “make room for the speaker’s voice and to help it arrive in its ‘authentic’ form” (Dobson, 2014, pp. 2, 26). Such listening is the entry place for dialogue, as the listener actively seeks to clarify, process what is heard, and make sense of it (Dobson, 2014; Evans & Vaandering, 2016). In this way, listening breaks through oppressive power and allows for dialogic co-creation of meaning (Dobson, 2014). Recognizing that we wished our methodology to hold apophatic listening at its center, we turned to listening methodologies.

The Listening Guide: A Voice Centered Relational Method

The Listening Guide (LG) was developed by Carol Gilligan and colleagues in the 1980s (Brown & Gilligan, 1991; Gilligan, 1982; Gilligan, 1982; Taylor et al., 1995) as a feminist, relational method meant to provide space for voices often silenced in research (Macaulay & Deppeler, 2020; Woodcock, 2016). The LG, with inherent flexibility, offers a “pathway into relationship” (Brown & Gilligan, 1991, p. 22) in which the researcher listens for the multiple voices expressed in one person’s experience (Gilligan et al., 2006). As a psychological method, the LG is attentive to what “can and cannot be spoken or heard” in people’s experiences (Gilligan & Eddy, 2017, p. 76). The attentiveness occurs through four distinct readings, called listenings, in which the researcher becomes attuned to various layers of a person’s voice, expressions, and experiences (Gilligan et al., 2006).

Two interrelated aspects of the LG connect with our own search for a methodology: curiosity and the role of the researcher. Researchers utilizing the LG are meant to approach their listenings without set assumptions and judgements. Gilligan and Eddy (2017) suggest that “in coming from a place of genuine curiosity or not knowing, the researcher becomes open not only to surprise or discovery but also to having one’s view of the world shaken” (p. 77). Being open to shaking your worldview also means that your worldview is acknowledged and available for scrutiny (Petrovic et al., 2015). Continual researcher reflexivity is identified as one of the key strengths of the LG (Petrovic et al., 2015; Woodcock, 2016).

As restorative researchers, we appreciate how the LG “reframes the research process as a process of relationships” (Gilligan & Eddy, 2017, p. 80). Yet, the LG was intended for—and has been used predominantly with—interview transcripts (Gilligan et al., 2006; Petrovic et al., 2015). So, we turned to more traditional discourse analysis methods to consider our approach with online comments.

Critical Discourse Analysis

One widely-accepted technique for analyzing text is discourse analysis. Discourse, comprising text and context, focuses on language as a social practice. This practice reflects existing reality and concurrently influences the way we think, act, and construct future reality.

Since discourse permeates all aspects of our social world, there are many entry points by which to analyze it. Critical discourse analysts are not only interested in how discourse works, but also in investigating its effects (Ainsworth & Hardy, 2004). Gee (2004) describes critical discourse analysis (CDA) as based on the idea that “social practices always have implications for inherently political things like status, solidarity, distribution of social goods, and power” (p. 33). While there are a variety of CDA approaches, their common aim is to analyze and expose social inequity and invisible power relations (Tracy, 2005). According to critical discourse analysts, external socio-political forces form people’s discursive behavior more than most people believe (Johnstone, 2008). Since people are often unaware of these forces, Fairclough (1989) discusses the role of CDA in raising people’s self-consciousness. Thus, CDA intends from the outset to empower participants through exposing the power dynamics inherent in social interactions and structures.

Gee (2011, p. 9) characterizes critical discourse analysts as wanting to “speak to and, perhaps, intervene in, social or political issues, problems, and controversies in the world.” Although this critical understanding of discourse analysis appealed to us for its focus on making power dynamics visible and empowering participants, the definition by Gee (2011) leaves little space for deep listening, for “making room for the speaker’s voice” (Dobson, 2014, p. 17) and for genuine dialogue.

Feminist Relational Discourse Analysis

Thompson et al. (2018) echo this critique of discourse analysis, highlighting the power relations inherent in the act of a researcher analysing participant voices for discursive meaning. Their work fits within a tradition of feminist poststructuralist and voice-centred research and activism, which seeks to distribute power and amplify the voices of those historically silenced. In 1989 Gavey suggested discourse analysis as a tool, within feminist poststructuralism, to “offer a way of understanding more of the complexities and contradictions that inhabit and shape our experience of this world” (Gavey, 2011, p. 184).

Thompson et al. (2018) created a model of Feminist Relational Discourse Analysis (FRDA) in which both the personal and the structural are accounted for, seeing discourses and voiced experiences as complementary. FRDA “aims to shed light on structural systems of power and the voices of those who go unheard within these” (Thompson et al., 2018, p. 99). Thompson et al. (2018) employed a two-phase approach to their analysis: 1. Poststructuralist discourse analysis, and 2. Analysis of emergent voices in relation to discourses. Building on Gilligan et al.’s (2006) Listening Guide, Thompson et al. (2018) present an integrated model for discourse analysis that connects the personal and relational with the structural.

Joining Them All together—Relational Critical Discourse Analysis

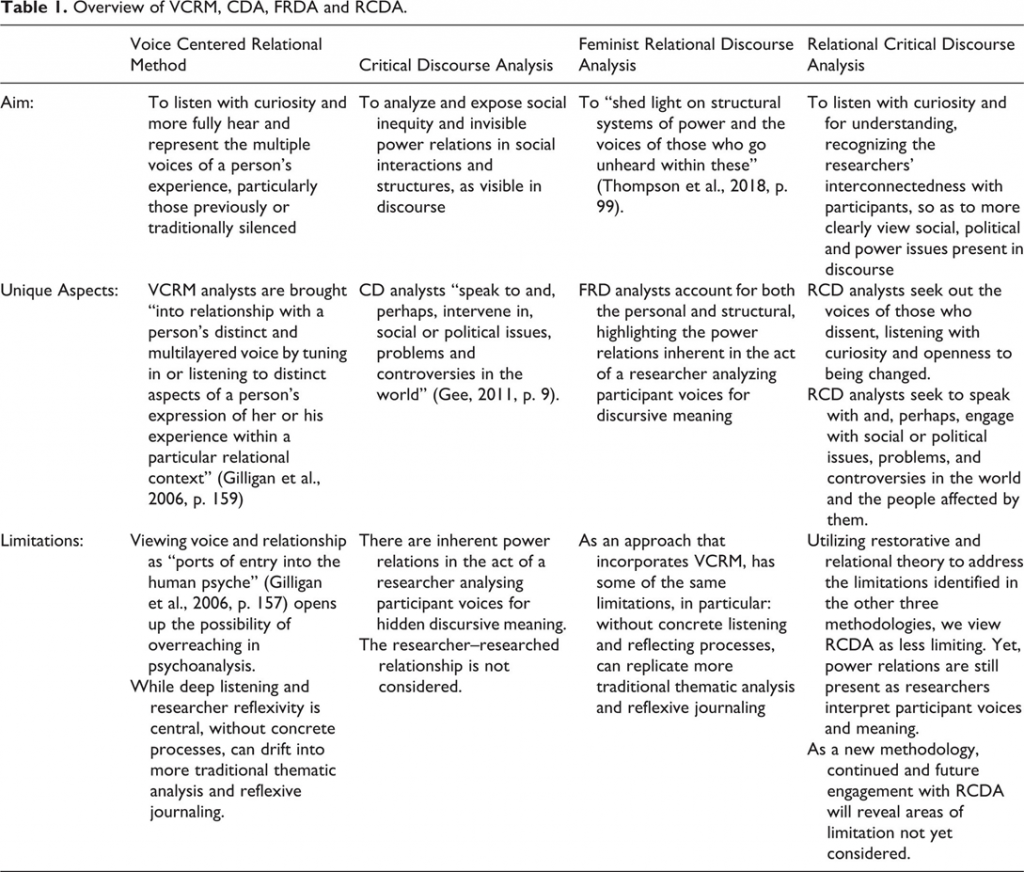

Our development of a methodology began with the strong underpinnings of restorative and relational theory and practice. On these underpinnings, we layered unique aspects of the established methodologies with which we engaged, conscious of using strengths in one to address limitations in another. Table 1 provides an overview of the aims of the three established methodologies (VCRM, CDA and FRDA), their unique aspects and their limitations. The final column of the table details the aims, uniqueness and limitations of RCDA, as a way to show both the connections and the distinctions between the four approaches.

From VCRM: we take an epistemology of curiosity and wonder; we hold as central the researcher researched relationship; we engage apophatic listening to guide both data collection and data analysis.

From CDA: we take an attention to discourse as a social and political practice; we view power as visible within social interactions and structures; we analyze texts (not only transcripts) in order to expose power and empower those affected.

From FRDA: we take the capacity to join focus on the personal and relational with focus on the structural; we view continual research reflexivity as imperative; we utilize the power of multiple readings or listenings in analysis.

The discussion section (p. 8) will detail more fully the unique offering of RCDA.

Relational Critical Discourse Analysis Application—A Case Study

A description of the particular case from which Relational Critical Discourse Analysis emerged will illustrate its nuances and potential. The case involved analyzing three news media reports and the resulting online comments regarding the experience of the Class of 2015 enrolled in the Dalhousie Dentistry school that participated in a restorative justice process.2 In December 2014, 14 female students uncovered abusive comments about themselves made by some of their male counterparts, 13 of whom had created and were part of a private Facebook page. The women approached the administration with their concerns and requested support for addressing the harm done using a restorative justice approach. Given that Nova Scotia had been engaged with restorative justice in various sectors of society since 1997 (Archibald & Llewellyn, 2006), and that Dalhousie University has a restorative justice approach as an option for addressing harm through its Student Conduct Office,3 this request was granted, and the process was launched. When the news outlets were alerted to the sexual harassment situation as well as the choice for restorative justice as the approach selected to address the situation, they began to report on the details. What resulted was an immediate public response to the university administration and its handling of the concerns through the media in the local community, across Canada, and beyond. In total, more than 3,600 news reports emerged in the 6-month period following the exposure of the Facebook page (Llewellyn, 2015b). Given the initial response to the situation and the provincial context in which it was occurring, we began to collect articles and comments recognizing that significant learning could emerge for the restorative justice community in particular if these were examined and analyzed. Always challenged to live out our restorative commitments in our own personal and professional lives, we began to discuss how to best proceed.

The method we decided to use for the case study, which was later developed into Relational Critical Discourse Analysis, followed these steps:

- Immerse, focus, position: After immersing ourselves in a multitude of articles and online comments, we focused our case study inquiry by framing it around two questions: (i) What does listening to public voices teach us about the mainstream perception of restorative justice? and (ii) How can understanding public perceptions inform the ways we, as a restorative justice community, communicate? (Vaandering & Reimer, 2019). In order to answer these questions, we recognized that the public would be responding to how the media was portraying restorative justice. Thus before listening to the online comments, we needed to also listen deeply to the words of the journalists. Not being able to examine all 3,600 articles and their responses, we made the decision to select only articles and their associated comments written in the first few days as a way to get a public gut-reaction to restorative justice. From these, we chose three articles—one local, two national—to do an in-depth analysis. From the start, the study questions we posed illustrate how we positioned ourselves directly in the study by choosing words like “teach us” and “inform the ways we…” recognizing that as proponents of restorative justice, we were fully part of and influenced by our field. In this way, we also were naming our positions of power, as academics who were recognizing how our positions typically provide distance from participants—a distance we were aiming to diminish. This process of immersing, focusing, and positioning for researchers personally places them in the midst of the context of the participants’ experience, while being explicit about potential limitations to understanding.

- Establishing the circle process: We then imagined ourselves as part of two dialogue circles: (i) A journalists’ circle and (ii) online commenters’ circle. This circle dialogue process is a core practice of restorative justice. Though there are various approaches4 in the field, several key components are common in most:

○ the presence of those directly involved sitting in a physical circle with no other furnishings between them;

○ establishing a common set of values and guidelines together that governs the time in circle;

○ a series of prompts or questions that each person present is invited to respond to and given the time and space needed to share their perspectives;

○ opportunity to “pass” and simply listen to what others say.

Having access only to the text written by each of these people, we adapted the circle dialogue process but maintained the essence of its purpose. By doing so, we took steps to making the text analysis as relational and humanizing as possible.

○ Individually, we each had a “circle meeting” with these two groups. We placed enough chairs in a circle for each participant, and placed their printed text on a chair designated for them. [Though we considered this to be a circle dialogue among the participants and ourselves as researchers, in reality, as a methodology for collecting and analyzing data, and to ensure a greater degree of validity, the two of us “met” separately with each group and then later came together to share what we heard and understood (Patton, 2002, p. 450).]

○ Then we established and wrote out a set of guidelines and values that we felt were core principles of restorative justice to which we would hold ourselves accountable in our imagined dialogue. These we placed on the floor in the middle of the circle. The values we chose included: respect, dignity, and concern. The guidelines emerging were stated as:

▪ I will honor each person speaking as worthy and interconnected;

▪ I will be fully present;

▪ I will listen with curiosity;

▪ I will accept that I might need to change;

▪ I will be honest.

○ Next we created questions/prompts to initiate dialogue in each meeting. These included:

▪ What are the understandings of restorative justice expressed?

▪ What emotions are expressed through these perceptions

▪ What is the potential impact of this understanding and emotions expressed?

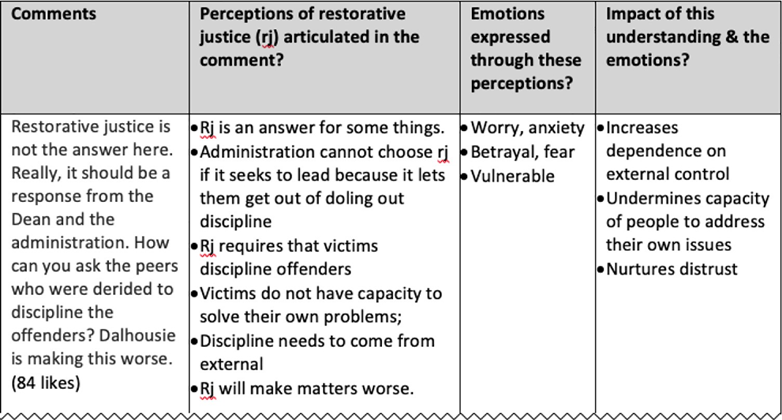

- Hearing participant insights: With values and guidelines in place, we began to listen to the voices of the participants as “heard” through the printed text. We conducted three rounds for each journalist and then, later, three rounds with each of the online commenters. A round consisted of us picking up and reading what the person wrote and then identifying details relating to the question we were focusing on for that round. To provide ourselves with the time and space to be fully present with each comment just as we would be in a physical circle, we recorded in writing what each “said” related to each question in a chart (see Figure 1 for the chart with the three rounds of questions and one online comment as an example). To complete the “listening” process, we then engaged in a reflexive internal dialogue with what we heard.

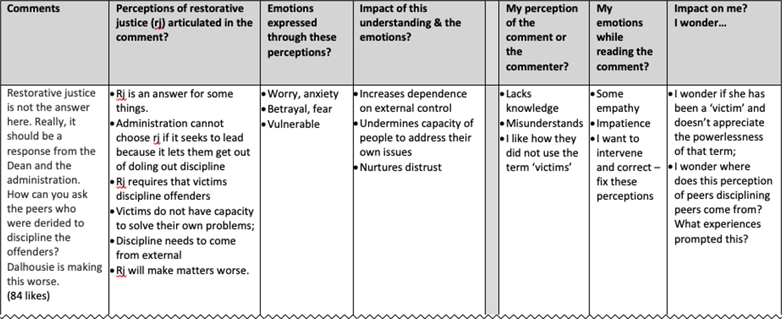

- Reflexive internal dialogue: Our responses to what we heard came by altering the questions/prompts slightly to focus on ourselves as researchers: (1) What is my perception of the comment and the commenter? (2) What are my emotions in listening to the comment? and (3) What impact does this have on me? The chart was expanded (Figure 2) to include these reflexive details. In this way, we were challenging ourselves to consider our immediate perceptions/gut-reactions in an explicit manner in much the same way as the journalists and commenters were doing when they first heard of the situation at Dalhousie University. When combined, we saw this as a way to honor the writers’ voices by respecting that their perspectives were valid enough to be considered carefully in terms of what they said and also in terms of the impact they had on us.

This honoring was also deepened when as co-researchers we “met” with each group separately, reading and responding to each piece of writing using the chart and then writing a data report (Patton, 2002, p. 450) for each article and their corresponding set of comments.

- Reflexive researcher dialogue: Coming together to share observations and responses, challenged us to identify, discuss and resolve discrepancies in our perspectives. We also analyzed the source of common themes, how these compared with dominant discourse of restorative justice in the academic and professional realms, and how these were influenced by our own context. At this stage, we began to experience the full impact of RCDA. We suddenly felt and understood ourselves to be in relationship with the participants, rather than observers of them, as we critically reflected on assumptions we held with wonder and curiosity. When we combined this with (i) apophatic listening—am I willing to change what I think? and (ii) honoring the speaker—can I accept this person’s perspective as reflective of their life experience?—this shift set us at the brink of deepening our own knowledge.

- Double Exposure: Results occurring from reflexive dialogue were twofold: (1) clear exposure of key, often misunderstood, elements of public perceptions as embedded within their reactions; i.e. restorative justice is a way for leaders to abdicate responsibility while victims carry the burden (2) clear exposure of assumptions we held as researchers (i.e., we assumed that commenters were more interested in punishing those who offended than in engaging with those who were harmed). The exposure of our own assumptions could then be used to inform as well as compare and contrast with the dominant discourse in the available literature in the field; i.e. our defensiveness turned to empathy as we began to hear within online comments a sincere desire to protect the vulnerable, rather than an outright rejection of restorative justice

- Recommendations: The final step includes proposing a path forward that allows for more informed dialogue in the field being studied, a step that will likely require the same nuanced curiosity, wonder, and apophatic listening to outside perspectives as we engaged in.

Lessons From the Use of Relational Critical Discourse Analysis

After completing the case study research using the steps outlined, it was the exposure of our own assumptions that confirmed for us that Relational Critical Discourse Analysis had potential for disrupting power structures that are not obvious at the start. Though research is intended to create or uncover new knowledge, in this case, we discovered that by listening to the dissenting perspectives of participants, the mirror was actually turned back onto the field of restorative justice, uncovering perspectives that are rarely acknowledged. In particular, we realized that (1) both the proponents and opponents of restorative justice were desirous of the same things—the safety and well-being of individuals and society and (2) the opponents were perceiving restorative justice approaches very similarly to how proponents were perceiving traditional justice approaches. In essence, the general public had, over time, picked up an understanding of restorative justice that directly contradicted the core principles and practices of restorative justice and were applying it to this particular context.

Although some of these findings may have emerged if we had utilized other methodologies, it is likely that the findings would have: 1) remained at a distance, not causing us as researchers to examine our own misperceptions; and 2) been easier to misinterpret since we might have characterized the participants as being misinformed.

In our case study, through Relational Critical Discourse Analysis, we were challenged to consider how/if we were employing apophatic listening and engaging with our own research results in a way that opened us to personal change. Specifically, we realized RCDA provided us with three key opportunities, which then led us to consider what RCDA might provide other researchers.

What Relational Critical Discourse Analysis Provided Us

- By engaging in a series of listenings—based on the physical restorative circle process—the analysis of the online comments was slowed down to a contemplative speed, which made apophatic listening more possible. We drew on the strengths of the structured physical restorative circle process, which focuses on mutual connection, understanding, and dialogue, in order to fully attend to the journalists’ articles and to each person’s written online comment. Each person’s comment was considered at length, as we went through the three rounds of listening to the written text, asking questions that moved us beyond the comment to the human being behind the comment (Barter & Sun, 2018).

- Our research was centered within an understanding of our interconnectedness. Rather than view the relationship as one of researcher and researched, restorative and relational theory asks that we, as the circle keepers/facilitators, view ourselves as active and equal participants within the research, connected, through our humanity, to one another. By seeing ourselves as part of a physical circle, there was a tangible sense of being part of the study, rather than an outside researcher looking in. Thus, as in the physical circle, the chance was heightened that we would be impacted by what we found. By questioning our own perceptions—through three additional rounds of listening—we were able to identify emotions and biases that might prevent the impact of the findings.

- A key component of restorative justice processes involves “seeing each other as a person with a story to tell” (O’Reilly, 2019, p. 159) so that the layering of multiple stories occurs to more fully comprehend a situation. In our case study, this meant intentionally seeking out commenters who viewed restorative justice as different than how we, as advocates, did: those whose comments portrayed concern that restorative justice might cause harm or be ineffective. We recognized that seeking out and engaging respectfully with those with dissenting voices would help us more fully understand and uncover significant lessons for the field of restorative justice.

What Relational Critical Discourse Analysis Could Provide Other Researchers

- While listening deeply to participants or to text is a desire of many qualitative analysts, there is rarely a concrete process to engage in. The image of a physical circle and the intentionality of rounds of questions provides researchers with an approach that is both methodologically practical and philosophically sound – based on restorative and relational philosophy. Although enacting a physical circle with written texts rather than actual people has limitations, the act assists researchers in engaging with texts at a more humane and relational level.

- By viewing the researcher as part of the circle process, there also exists an engaging process for reflexivity. Often the default for reflexivity is journaling, which can become an empty and rushed activity. Slowing down to be part of three rounds of self-listening presents the opportunity for more engaged and thoughtful reflection by intentionally considering our cognitive and emotional responses to each comment and filling in the chart (see Figure 2) independently.

- Reflexivity is also not seen as a lone undertaking. As with many methodologies, having more than one researcher involved increases both the credibility and potential depth of analysis. RCDA is intentionally relational; when possible, we suggest ensuring that at least two researchers are involved. As participants of the circle, co-researcher reflexivity can then be engaged in. The sharing and comparing of individual insights make for richer collective understandings.

- For whatever is being studied, intentionally inviting dissenting voices as we did in selecting comments that were not supportive of restorative justice. Such voices that depart from the researcher’s assumptions encourage more nuanced understanding of the area being researched and deeper insight into the researcher’s biases.

As a counter-cultural approach, Relational Critical Discourse Analysis holds the potential to slow research down, intentionally invite unfamiliar or dissenting voices, listen for understanding and recognize and disrupt taken-for-granted power structures. It is important here to pause for a caution from Gavey (2011), writing about Feminist Poststructuralism and Discourse Analysis: “But methods and theories of any kind, although helpful or even necessary starting points, can operate to discipline thinking in ways that can close down careful and creative reflexive considerations of what we might do in the name of research and why” (p. 186).

In the next section, we take Gavey’s (2011) caution and reflect carefully on what we might do with Relational Critical Discourse Analysis and why.

Significance

Developed and employed in a pre-pandemic time, and re-examined during the Summer 2020 resurgence of civil rights in the US and Canada, this methodology demonstrates its capacity for creating opportunity for academics waking up to privilege of any kind to deconstruct research and research(er) practices that contribute to the perpetuation of systemic oppression. Though not directly connected to issues of race in our case study, the validity of Relational Critical Discourse Analysis is strengthened in how it aligns well with the components of critical research (CR) as outlined by Darder (2015), who describes the work of bicultural researchers decolonizing methodologies in an effort to demonstrate and provide alternatives to mainstream methodologies produced in the context of hegemonic epistemologies which perpetuate oppression. In particular, she outlines how CR must address ideology, hegemony, critique, counter-hegemony, an alliance of theory and practice, and conscientization. What follows is a brief description of each of these, how RCDA complies, and then its promise for future research.

Ideology: Critical Research always contends that there is a set of ideas that shape how researchers make sense of the world (Darder, 2015, p. 68). Relational Critical Discourse Analysis exposed for us a set of ideals/ideology that, until we were doing the analysis, we could not/had not identified. This occurred because we used apophatic listening within the physical circle process that we replicated, which helped us hear the perceptions of the dissenting participants as if they were speaking directly to us. This challenged our beginning (unidentified?) assumptions that what we understood would be supported by the research we were doing. Though this defies reliable research, we identify that in spite of our best intentions, researchers have a vested interest in work for which they advocate and thus come to the work with bias. For future research, researchers identifying their personal/professional investment in a topic is a starting point for their work. Then they will more likely identify which perspectives might be the dissenting voice, and engage in listening that will hear participants speaking to them directly.

Hegemony: Critical Research disrupts research that exists to support the status quo (Darder, 2015, p. 68). In our case study, supporting the status quo within the restorative justice field would have meant dismissing negative public perceptions as misinformed. Instead, Relational Critical Discourse Analysis uncovered public perceptions of restorative justice that echo how advocates describe the mainstream justice system; thus listening deeply revealed hidden common interests and common fears. To date, this had not been recognized in the literature in other studies conducted with different methodologies. This finding was possible because our analysis required that we consider not just how participant perspectives and feelings impacted their understanding, but also how we, as researchers, might be biased against participants with dissenting views. For future research, researchers intentionally making note of the impact of their participants’ perceptions and emotions on them has the potential to disrupt assumptions that are tied to their privilege.

Critique: Critical Research interrogates assumed power structures and believes change occurs by (1) naming our own reality (2) problematizing our own reality (3) positing new possibilities for change (Darder, 2015, p. 68). Relational Critical Discourse Analysis resulted in exactly this, identifying how we as restorative justice advocates (the assumed power structure with restorative justice knowledge) came to question our assumptions by naming and problematizing our own reality and then recognizing the work that is required by the field of restorative justice, rather than by those opposing restorative justice. For future research, these three steps can be intentionally engaged with as a framework for the research project. This is important in that the starting point of the study will always begin with interrogating the researcher’s personal investment into the work.

Counter-hegemony: Critical Research works to dismantle and transform existing oppressive conditions (Darder, 2015, p. 68). One goal of restorative justice is to provide a voice for all people to express their needs in a given situation so healing could emerge. In our study, Relational Critical Discourse Analysis uncovered how this goal will never be accomplished until those of us within the restorative justice field listen apophatically to how restorative justice is being perceived and understood; we need to accept responsibility for addressing the gaps in how restorative justice turns principles into practice. This insight occurred because RCDA recognizes the individual within the collective where social inequities and invisible abuses of power occur in the common everyday experience. For future research, the act of listening with an openness to possibly needing to change, sets up a more authentic opportunity for reciprocal learning and growth.

Alliance of theory and practice: Critical Research ties theory to practice for the sake of the most vulnerable. It is attentive and responsive to their actual experiences and is characterized by being flexible and ready to change as deemed necessary by each particular situation (Darder, 2015, p. 68). Drawing on Freire’s (1970) concept of praxis, with Relational Critical Discourse Analysis, the researcher does not stand apart from or outside of the participant. This ensures that the challenges that arise are carried together. In our study, the alliance of theory and practice, which is often recommended in the field (Bretherton & Law, 2015; Toews & Zehr, 2003), compelled us as co-researchers to hold each other accountable to the principles of restorative justice: that everyone is inherently worthy and that we are all interconnected (Evans & Vaandering, 2016). This led to a deeper understanding of how the dissenting voice needed to be recognized as belonging to human beings whose perspectives were worthy of consideration and often coming from a desire, like ours, to uphold the well-being of all. This then opened up a need for clarity for future communication by advocates for the general public. For future research, this is most significant in that the onus of responsibility for acting on research recommendations includes the researcher(s) who then cannot simply provide a report/paper and then move on to other things.

Conscientization: Critical Research deliberately supports conscientization (Freire, 1970), “the development of social consciousness and an expanding sense of human interactions” (Darder, 2015, p. 69). Its intention is to work collaboratively with those with lived experience, to construct knowledge that results in a “collective emancipatory action that transforms existing conditions of inequality and injustice in schools and society” (Darder, 2015, p. 69). Ultimately Relational Critical Discourse Analysis embodies conscientization in that like restorative justice itself, the dissenting voice is honored as significant for the thriving of all. In our study, one of our findings included how both those advocating for and resisting restorative justice as a way for addressing the harm done shared a passionate desire that people not be (ab)used or harmed. We also found that misunderstandings of restorative justice provided fodder for perpetuation of harm through the current oppressive systems. When research findings uncover misperceptions of all involved that perpetuate injustice and inequality, then greater potential for collaboration and solidarity emerges. For future research, this is significant in that ultimately, RCDA is the practice of conscientization, regardless of the focus of study.

Next Steps in the Development of Relational Critical Discourse Analysis

As a new methodology, there is substantial work to be done for varied critical researchers to apply Relational Critical Discourse Analysis to their own fields and within their own studies. We have much yet to learn about the potential and the limitations of RCDA. We offer this overview of how we developed and employed RCDA as an invitation to others to engage with, critique and strengthen RCDA as a critical peace —and potentially decolonizing—methodology.

At a time when decolonization, Indigenization, and critical race theories and methodologies are being developed, in particular, by bicultural, subaltern academics (Darder, 2015), it is important that white, western-born researchers learn to observe and listen apophatically to insights that have rarely been considered or valued in the past. As such, we need to not rush into these methodological spaces too quickly as history has shown how readily such work is then co-opted and recolonized. The work we must do and can do through Relational Critical Discourse Analysis, which is grounded in restorative justice principles and practices, creates space for the stories of participants, stories that are told using “ordinary” words that grow in meaning when joined with the stories of the researchers. When this happens, we move beyond pedagogies of deliberation where the context of the story-tellers is ignored and deemed unnecessary and instead engage in counter-narration pedagogies that challenge those of us with fixed, assumed positions to realize there are different ways of living and seeing the world (Gibson, 2020). This can then result in an interrogation of previous notions of success, as we discovered when using RCDA. Ultimately new worldviews can emerge (O’Reilly, 2019) that hopefully will include an understanding that “every worldview is a way of seeing, but also a way of not seeing” (Docherty, 2020).

Relational Critical Discourse Analysis is a methodology that is significant particularly for researchers who are used to making assumptions about knowledge, used to researching the “other,” and used to being beneficiaries of the sacrifices of others. It is a methodology that draws on the truths inherent in restorative justice, prioritizes the voices ignored, unheard, or dissenting, and comes to accept discomfort and no final resolution/restoration but only a turning point in the story at this time (O’Reilly, 2019).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

dorothy Vaandering: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6553-3022

Kristin E. Reimer: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2627-3598

Authors’ Contribution

Both authors contributed equally to this work.

Notes

- For details on this study see Vaandering and Reimer (2019).

- There were a total of 38 students in the core 4-year program at the time; 29 of them participated in the restorative justice process—12 of the 13 men who were members of the Facebook group, 14 women, and three other men in the program not involved in the Facebook group. For details on this particular case and the results of the restorative justice process, see the 72 page report: https://www.dal.ca/cultureofrespect/background/report-from-the-restorative-justice-process.html

- Student Conduct Office—Student Rights & Responsibilities

- See Boyes-Watson and Pranis (2014) and DeWolfe and Geddes (2019) for in-depth descriptions of circle dialogue approaches.

References

Ainsworth S., Hardy C. (2004). Critical discourse analysis and identity: Why bother? Critical Discourse Studies, 1(2), 225–259. Crossref.

Archibald B., Llewellyn J. (2006). The challenges of institutionalizing comprehensive restorative justice: Theory and practice in Nova Scotia. Dalhousie Law Journal, 29, 297–343.

Barter D., Sun R. (Speakers). (18 December 2018). Conflict in the comments [Audio podcast]. Retrieved January 15,

2019, from https://restorativejusticeontherise.org/conflict-in-the-comments-with-dominic-barter-rivera-sun/

Bell D. (1995). Who’s afraid of critical race theory? University of Illinois Law Review, 1995(4), 893 ff.

Bingham C., Sidorkin A. M. (Eds.) (2004). No education without relation. In Kincheloe J. L., Steinberg S. R. (General Eds.), Counterpoints series: Studies in postmodern theory of education (Vol. 259). Peter Lang.

Boyes-Watson C., Pranis K. (2014). Circle forward: Building a restorative school community. Living Justice Press.

Bretherton D., Law S. F. (Eds.) (2015). Methodologies in peace psychology: Peace research by peaceful means.

Brown L. M., Gilligan C. (1991). Listening for voice in narratives of relationship. In Tappan M. B., Packer M. J. (Eds.), Narratives and storytelling: Implications for understanding moral development (pp. 43–62). Jossey-Bass Inc.

Cole D. (2020). The skin we’re in: A year of black resistance and power. Doubleday Canada.

Crouch A. (2013). Playing god: Redeeming the gift of power. InterVarsity Press.

Darder D. (2015). Decolonizing interpretive research: A critical bicultural methodology for social change. The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 14(2), 63–77.

DeWolfe T., Geddes J. (2019). The little book of racial healing. Skyhorse Publishing.

Dobson A. (2014). Listening for democracy: Recognition, representation, reconciliation. Oxford University Press.

Docherty J. (2020). Worldviewing [Peacebuilder Podcast]. https://emu.edu/now/news/2020/peacebuilder-podcast-worldviewing-with-jayne-docherty/

Evans K., Vaandering D. (2016). The little book of restorative justice in education. Skyhorse Publishing.

Fairclough N. (1989). Language and power. Longman.

Freire P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Seabury.

Gavey N. (2011). Feminist poststructuralism and discourse analysis revisited. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 183–188. Crossref.

Gee J. P. (2004). Discourse analysis: What makes it critical? In Rogers R. (Ed.), An introduction to critical discourse analysis in education (pp. 19–50). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Crossref.

Gee J. P. (2011). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Gibson M. (2020). From deliberation to counter-narration: Toward a critical pedagogy for democratic citizenship.

Theory & Research in Social Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2020.1747034

Gilligan C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

Gilligan C., Eddy J. (2017). Listening as a path to psychological discovery: An introduction to the listening guide.

Perspectives and Medical Education, 6, 76–81. Crossref. PubMed.

Gilligan C., Spencer R., Weinberg M. K., Bertsch T. (2006) On the listening guide: A voice-centred relational method. In Rhodes J. E., Yardley L., Camic P. M. (Eds.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 157–172). American Psychological Association.

Hendry R. (2009). Building and restoring respectful relationships in schools: A guide to using restorative practice.

Routledge.

Johnstone B. (2008). Discourse analysis. Blackwell publishers.

Leavy P. (Ed). (2014) The Oxford handbook of qualitative research. Oxford University Press. Crossref.

Llewellyn J. (2011). A relational vision of justice: Revisioning justice. Restorative Justice Week. Correctional Service of Canada.

Llewellyn J. (2015b). The Dalhousie dentistry school: A restorative justice case study [Audio presentation]. http://adric.ca/news/2057-2/

Llewellyn J., Morrison B. (2018). Deepening the relational ecology of restorative justice. The International Journal of Restorative Justice, 1(3), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.5553/ijrj/258908912018001003001

Llewellyn K. R., Llewellyn J. J. (2015). A restorative approach to learning: relational theory as feminist pedagogy in universities. In Penny Light T., Nicholas J., Bondy R. (Eds.), Feminist pedagogy in higher education: Critical theory and practice (pp. 11–32). Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Macaulay L., Deppeler J. (2020). Perspectives on negative media representations of Sudanese and South Sudanese Youths in Australia. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 41(2), 213–230. Crossref.

McCue D. (2020, June 7). Ask me anything with El Jones: People who deny racism exists in Canada are ‘like people who deny climate change’ [Radio Broadcast]. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/checkup/what-advice-do-you-havefor-the-graduating-class-of-2020-1.5599833/people-who-deny-racism-exists-in-canada-are-like-people-who-denyclimate-change-says-el-jones-1.5600237

Miller J. B., Stiver I. P. (1997). The healing connection: How women form relationships in therapy and in life. Beacon Press.

Nadjiwan H. (2008). Stolen children: Truth and reconciliation concert. www.cbc.ca/radio2/cod/concerts/20080605stoln

O’Reilly N. (2019). Tell me the story: Marginalization, transformation, and school-based restorative justice.

International Journal of Educational Research, 94, 158–167. Crossref.

Patton M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Sage Publications.

Petrovic S., Lordly D., Brigham S., Delaney M. (2015). Learning to listen: An analysis of applying the Listening Guide to reflection papers. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14, 1–11. Crossref.

Pranis K., Stuart B., Wedge M. (2003). Peacemaking circles: From crime to community. Living Justice Press.

Ross R. (1996). Returning to the teachings: Exploring aboriginal justice. Penguin.

Schwartz H. L. (2019). Connected teaching: Relationship, power and mattering in higher education. Stylus Publishing.

Taylor J. M., Gilligan C., Sullivan A. (1995). Between voice and silence: Women and girls, race and relationship.

Harvard University Press.

Thompson L., Rickett B., Day K. (2018). Feminist relational discourse analysis: Putting the personal in the political in feminist research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 15(1), 93–115. Crossref.

Toews B., Zehr H. (2003). Ways of knowing for a restorative worldview. In Weitekamp E. G. M., Kerner H.-J. (Eds.), Restorative justice in context (pp. 257–271). Willan Publishing.

Tracy K. (2005). Reconstructing communicative practices: Action-implicative discourse analysis. In Fitch K. L., Sanders R. E. (Eds.), Handbook of language and social interaction (pp. 301–319). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Vaandering D. (2015). Critical relational theory. In Hopkins B. (Ed.), Just theories. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Vaandering D., Reimer K. (2019). Listening deeply to public perceptions of restorative justice: What can researchers and practitioners learn? The International Journal of Restorative Justice, 2(2), 186–208. Crossref.

Waks L. J. (2010). Two types of interpersonal listening. Teachers College Record, 112(11), 2743–2762.

Wood M., Liebenberg L. (2019). Considering words and phrasing in the way we write: Furthering the social justice agenda through relational practice. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–4. Crossref.

Woodcock C. (2016). The listening guide: A how-to approach on ways to promote educational democracy. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 15(1), 1–10. Crossref.

Contact

dorothy Vaandering, Memorial University of Newfoundland,

St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada A1C 5S7.

Email: [email protected]

Citation

Vaandering, dorothy, and Kristin E. Reimer. “Relational Critical Discourse Analysis: A Methodology to Challenge Researcher Assumptions.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 20, Jan. 2021, p. 160940692110209. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211020903.

Copyright License

- Title: “Relational Critical Discourse Analysis: A Methodology to Challenge Researcher Assumptions”

- Authors: “dorothy Vaandering and Kristin E. Reimer”

- Source: “https://journals.sagepub.com/”

- License: “CC BY 4.0”