Rigor, Transparency, Evidence, and Representation in Discourse Analysis: Challenges and Recommendations

Abstract

Discourse analysis is an important qualitative research approach across social science disciplines for analyzing (and challenging) how reality in a variety of organizational and institutional arenas is constructed. However, the process of conducting empirical discourse analyses remains challenging. In this article, we identify four key challenges involved in doing discourse analysis and recommend several “tools” derived from empirical practice to address these challenges. We demonstrate these recommendations by drawing on examples from an empirical discourse analysis study we conducted. Our tools and recommendations aim to facilitate conducting and writing up discourse analyses and may also contribute to addressing the identified challenges in other qualitative methodologies.

Keywords: discourse analysis, rigor, transparency, evidence, representation, qualitative research, quality.

A growing body of research across social science disciplines has shown the remarkable contributions of discourse analysis to producing knowledge about how meaning is created in various social, organizational, and institutional settings. Discourse analysis, both as theoretical and methodological approach, has thus been established as important and highly valuable for social science research (e.g., Gee, 2005; Gee & Greene, 1998; Jaworski & Coupland, 2006a; Phillips & Hardy, 2002; Phillips, Lawrence, & Hardy, 2004; Rogers, 2004). Accordingly, methodological advances have contributed to the further proliferation and recognition of discourse analysis. Nevertheless, the empirical analysis of discourses remains challenging (e.g., Hardy, 2001; N. Phillips, Sewell, & Jaynes, 2008) and researchers pursuing discourse analyses need to resolve an array of key methodological challenges in their work. In this article, we identify key challenges of qualitative research involved in the context of discourse analysis and we recommend ways for addressing these challenges in doing empirical discourse analysis.

A synthesis of the literature suggests that key challenges of qualitative research include conducting data analyses that are systematic and properly informed by their respective theoretical and epistemological underpinnings, maintaining transparency of methodological processes, providing evidence that warrants knowledge claims, and representing data and analysis in ways that substantiate the results and are suitable for publication format (American Educational Research Association [AERA], 2009; Pratt, 2008; Ragin, Nagel, & White, 2004). These challenges are particularly important in the context of conducting discourse analysis, because discourse analysis emphasizes the discursive construction of social realities through texts, is highly interpretive in nature, and relies on previous theory (Hardy, 2001; Luke, 1996; N. Phillips & Hardy, 2002). Hence, in this article we focus on how these key challenges of doing qualitative research surface in the context of discourse analysis and suggest specific tools to address them, which we will illustrate through examples from an empirical discourse analysis of strategic management discourse in public education we have conducted. In doing so, we aim to provide guidance to other researchers to cope with these challenges. Moreover, we believe that an open debate of these challenges and how to address them in discourse analysis research can facilitate the quality and trustworthiness as well as the proliferation of empirical discourse analyses in social science research. More generally, we also aim to contribute to the qualitative research methodology literature on addressing the identified key challenges. In the next section, we provide a brief theoretical background on discourse analysis, followed by a section on the challenges of discourse analysis and a section on the proposed tools to address those challenges.

Theoretical Background: Text, Discourse, and Discourse Analysis

A burgeoning literature has firmly established the value of discourse-centered approaches to research in the social sciences. These various discourse analysis approaches draw on theories and methods developed in literature across different disciplines (for an extensive overview of discourse theory and method across disciplines, see for example, Grant, Hardy, Oswick, & Putnam, 2004; Jaworski & Coupland, 2006a; Schiffrin, Hamilton, & Tannen, 2001; van Dijk, 1985). This literature has developed a wide range of conceptualizations of discourse, and accordingly, a wide variety of discourse analytic approaches that may differ in important ways (see also Alvesson & Kärreman, 2001; Fairclough, 1992; Gee, 2005; Hammersley, 1997; Jaworski & Coupland, 2006a; Johnstone, 2002). Therefore, we begin by clarifying our use of terminology to situate our article’s purpose and contribution in the literature. Despite various definitions of discourse in the literature, a consistent emphasis lies on “language in use,” and discourse is broadly defined as language use in social settings that is mutually constitutive with social, political, and cultural formations (Jaworski & Coupland, 2006b). Discourse analysis, then, is the study of language in use in these settings. The literature has distinguished micro (or little “d”) and macro (or big “D”) discourses and accordingly micro and macro discourse analyses (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2001; Gee, 2005; Luke, 1996; K. Tracy & Mirivel, 2009). The former focus on how language is used in social settings (see, for example, Elizabeth, Anderson, Snow, & Selman, 2012; Macbeth, 2003), whereas the latter analyze texts with the understanding that they always involve “language plus ‘other stuff’” (Gee, 2005, p. 26) and see texts also as instances of discursive and social practices (Fairclough, 1992). Macro approaches to discourse analysis in no small part owe their intellectual heritage to the seminal work of Michel Foucault, who considers discursive practices to be constitutive of knowledge and social subjects, and emphasizes the relationship between discourse and power (Foucault, 1972, 1977, 1980).

The recommendations and discussions in this article are based on the tenets of macro-level (big “D”) discourse analysis. This line of macro-level discourse analysis starts from the premise that organizations, institutions, societies, and cultures are discursively constructed through texts (e.g., Alvesson & Kärreman, 2001; Fairclough, 1992; Luke, 1996), and consequently examines how discourse produces these elements of the social world by focusing on the performative functions of discourse, that is, what discourse is doing and achieving (Wood & Kroger, 2000). This can be pursued following descriptive or critical goals (Fairclough, 1985, 1995). Descriptive approaches to discourse analysis study language use without investigating its connections to social structures. Critical approaches to discourse analysis assume that ideologies and power structures shape the representation of “knowledge” or “facts” about “reality” from the perspective of a particular interest with the objective to naturalize ideological positions, that is, to win their acceptance as being nonideological and “common sense” by hiding them behind masks of naturalness and/or “science” (Fairclough, 1985; Fournier & Grey, 2000). Based on this assumption, critical approaches aim to denaturalize discourse to show how taken-for-granted, naturalized ideas are unnatural and ideological and how they are related to social structures (Fairclough, 1985, 1995; Kress, 1990; van Dijk, 1993). Discourses define particular meanings associated with sets of concepts, objects, and subject positions, thereby shaping social settings, their power relations, and what can be said and by whom (Hardy & Phillips, 2004). Discourses are not merely talk; they are performative and produce particular versions of social reality to the exclusion of other possibilities, thereby substantially shaping socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural conditions and processes (e.g., Chia, 2000; Fairclough, 1992, 2003; Gee, Hull, & Lankshear, 1996). Because discourses are not material, and thus not directly accessible, discourse analysis investigates discourses by studying the texts—that is, instances of written or spoken language with coherence and coded meanings (Luke, 1996)—constituting them (Fairclough, 1992; N. Phillips et al., 2004; Wood & Kroger, 2000). A text is a repository of sociocultural practices and their effects (Kress, 1990) as well as a material manifestation of a discourse (Chalaby, 1996); hence texts constitute the data and objects of analysis for discourse analysis studies. Despite the progress in the evolution of various types of discourse analysis and the rich methodological and empirical literature on discourse analysis, conducting empirical discourse analysis remains a challenging enterprise. In the following section, we identify four interrelated key challenges involved in conducting and reporting discourse analysis, followed by five tools for overcoming these challenges.

Challenges in Conducting Discourse Analysis

The diversity of epistemological positions, theoretical frameworks, and methods creates challenges for judging the quality and trustworthiness of knowledge produced by qualitative research (Anfara, Brown, & Mangione, 2002; Denzin, 2009; Denzin & Lincoln, 2000; Guba, 1990; Hammersley, 2007). Challenges in doing qualitative research include conducting systematic analyses, explicating qualitative research processes, substantiating results, and describing and representing data and methodological processes (AERA, 2006, 2009; Anfara et al., 2002; Constas, 1992; Eisner, 1981). Hence, starting with seminal contributions such as Lincoln and Guba’s (1985, 1986) work, a wealth of literature has contributed to improving our knowledge of how researchers can engage in rigorous empirical qualitative research, and of how they can persuade audiences of the trustworthiness of their results (e.g., Lincoln, 1995; Morse, Barrett, Mayan, Olson, & Spiers, 2002; D. Phillips, 1987; S. Tracy, 2010). Although the challenges we identify in this article are relevant for qualitative research generally, criteria for judging what is good or valid knowledge should be coherent with epistemological and theoretical assumptions of a methodology (Burrell & Morgan, 1979; Crotty, 1998). Furthermore, the analysis procedures, writing practices, and methodological conventions through which the challenges can be addressed are specific to a certain methodology; therefore, our discussion of these challenges and our recommendations for how to address them are tailored to discourse analysis.

Regardless of one’s theoretical commitments or the content of a study, a researcher conducting an empirical discourse analysis is likely to face the challenges of how to (a) perform a systematic discourse analysis that goes beyond descriptive “analysis” of texts in order to focus on the hidden and naturalized functions the discourse fulfills; (b) do the analysis transparently, which is particularly challenging considering discourse analysis’s interpretive focus on the constructive effects of texts; (c) warrant with appropriate evidence the study’s rigorous and systematic analysis process as well as its knowledge claims; and (d) represent the process and results of discourse analyses to accomplish transparency and warranting of evidence, while producing sufficiently succinct manuscripts. These challenges are interrelated and usually co-occur in a study; however, in order to clearly present and create awareness of the respective challenges, in this article, we present them consecutively.

Systematic and Rigorous Analysis

Social science research distinguishes itself from casual observation by arriving at trustworthy inferences through applying systematic inquiry procedures (King, Keohane, & Verba, 1994). Thus, a basic demand for all qualitative research has been for it to be systematic and rigorous, although conceptions of rigor are rooted in and therefore differ across paradigms of qualitative research (Hammersley, 2007). On a general level, in qualitative research, rigor is accomplished through attentiveness to the research process in practice (Davies & Dodd, 2002; Ryan, 2004). Rigorous analysis of qualitative data requires that chosen analytical processes are appropriate for investigating the phenomenon of interest and analyzing the relevant data from the vantage point of the researcher’s theoretical and epistemological commitments. Thus, a core methodological challenge for qualitative approaches is conducting data analysis by applying frameworks that enable rigorous analyses informed by and coherent with the respective epistemological and theoretical assumptions underlying and guiding a study (Denzin, 2009; Howe & Eisenhart, 1990).

The overarching objective of discourse analysis is to understand how a discourse performs its various functions and effects to construct a certain reality (Gee, 2005; Wood & Kroger, 2000). To explore the constructive effects of texts constituting discourses, discourse analysts rely heavily on interpretation (Hardy, 2001; N. Phillips & Hardy, 2002). Although interpretation and judgment—which will necessarily (if not intentionally) be shaped by an individual researcher’s epistemological assumptions and values (Harding, 1987, 1996)—are necessary, applying systematic analysis methods and conducting rigorous analyses grounded in epistemological and theoretical assumptions of discourse analysis aids in establishing the trustworthiness of these interpretations and rendering defensible knowledge claims (Gee, 2005; Wood & Kroger, 2000). In doing so, researchers need to find a delicate balance between different analytical extremes, that is, they need both (a) to aim to engage in systematic and rigorous analysis and interpretation processes without succumbing to pressures of dominant positivist approaches for standardizing the process and (b) to build on a sound understanding of theory and political positions rather than face-value reading of data, while at the same time avoiding over-interpretation and forcing metanarratives on the data (Grant & Hardy, 2003).

Researchers have tended to devise idiosyncratic analysis frameworks—ideally based on discourse analysis’s theoretical tenets—to respond to these challenges. Researchers advocating for idiosyncratic approaches claim they offer benefits such as being able to accommodate the emergent aspects of data analysis, allowing researchers to avoid emerging quasi-scientific methodology discourses that leave little room for reflexivity, and allowing them to avoid becoming too standardized and mechanical in their application (Grant & Hardy, 2003). However, it is also recognized that idiosyncratic approaches make discourse analyses more daunting, and furthermore create difficulties in establishing their trustworthiness and merit to evaluators and readers (N. Phillips & Hardy, 2002; N. Phillips, Sewell, & Jaynes, 2008). More generally, Lincoln and Guba (1985) cautioned qualitative researchers that the emergent nature of qualitative research designs “should not be interpreted as a license to engage in undisciplined and haphazard ‘poking around’” (p. 251). In sum, a key challenge for discourse analysts is to study discourses in a systematic and rigorous manner that is consistent with its epistemological and theoretical assumptions.

Transparency of Analysis

Although systematic and rigorous analysis is vital for enhancing a study’s trustworthiness, it is also vital that researchers explicitly document and communicate their analysis procedures (Anfara et al., 2002; Constas, 1992; Harry, Sturges, & Klinger, 2005). Hence, building on the first challenge, the second key challenge for enhancing trustworthiness and quality of a discourse analysis is to transparently communicate the analysis process, thereby demonstrating its rigor.

Efforts toward greater transparency have been contrasted with those fostering mystique and magic-like operations among artists who fear that demystifying their work for their audience may threaten rather than enhance the product of their work (Freeman, deMarrais, Preissle, Roulston, & St. Pierre, 2007). This is important because qualitative research practices that are shrouded in mystery are likely to hamper their evaluation and to create confusion among readers (AERA, 2006; Ryan, 2004). Put differently, greater transparency enables readers to evaluate a study’s rigor and the trustworthiness of its results. Therefore, a need for transparency in qualitative research has been recognized as crucial, and authors have been challenged to transparently convey the processes and decisions involved in moving from design and data analysis, through to results and interpretations (AERA, 2006, 2009; Constas, 1992; Harry et al., 2005). Indeed, it has been argued that although complete transparency of methodological processes and decisions can never be achieved, striving for a high degree of transparency is vital for judging qualitative research across the social sciences (Hammersley, 2007; Lamont & White, 2005).

Anfara et al. (2002) observed that opposition to public disclosure of research processes might be rooted in difficulties of qualitative researchers to articulate how they arrived at their interpretations. Thus, methodological developments that help to demystify the research process and to transparently communicate the methodological procedures can facilitate empirical research itself. In discourse analysis, this involves demonstrating in detail the process by which researchers moved from texts constituting the discourse to results (i.e., their interpretations of meanings and functions constructed through this discourse), as well as disclosing the decisions made in this process. The challenge of transparency is compounded by the challenge of representing complex analysis and interpretation processes by visual or textual means, which inevitably have to remain simplifications of the actual ways researchers arrive at their interpretations (Anfara et al., 2002; Harry et al., 2005). We discuss issues of representation as the fourth challenge below.

Substantiation of Claims with Evidence

In addition to conducting systematic and rigorous analyses, and doing so transparently, a third challenge for qualitative inquiry is to warrant a study’s claims and results by providing appropriate evidence to convince readers of its credibility and trustworthiness (Freeman et al., 2007; D. Phillips, 1987). What is appropriate evidence varies with a researcher’s theoretical perspective (Fisher, 1977; Lincoln, 2002) and a given research community’s standards (Bernard, 1994; D. Phillips, 1987). Thus, a key challenge for qualitative research in general, and for discourse analysis in particular, is deciding what counts as evidence and how to present that evidence to substantiate claims (AERA, 2006; Denzin, 2009).

Warranting knowledge claims involves two types of evidence: (a) evidence of a systematic and rigorous analysis process, and (b) evidence of the substantive basis of results and knowledge claims. To begin with the former, appropriate evidence regarding the analysis process is necessary to convince readers that a study’s results and conclusions are credible (AERA, 2006), a widely endorsed criterion for judging the quality of qualitative research (Bryman, Becker, & Sempik, 2008). For example, Anfara et al. (2002) have highlighted that although researchers frequently refer to qualitative techniques such as triangulation and member checks in their manuscripts, rarely do they provide evidence of how exactly these were achieved. Transparency of process, paired with sufficient evidence of its rigor, would serve to warrant for process and thereby demonstrate the study’s rigor. Discourse analysis faces particular challenges in warranting for analysis process. As interpretive analysis of the meaning of language in context (as opposed to thematic or structural analysis of textual data), it lacks formulaic or mechanical approaches applicable across studies. For this very reason, research reports should include disclosure of analysis and decision processes supported with proper evidence to convince readers and evaluators of their rigor.

With regard to the second type of evidence, warranting for knowledge claims involves identifying, selecting, and presenting appropriate data evidence to convince an audience of the trustworthiness of knowledge claims (AERA, 2006, 2009; D. Phillips, 1987; Wolcott, 2001). Systematic data analysis turns data into evidence that is directed toward a certain question or argument (Lincoln, 2002). Knowledge claims in discourse analysis are based on insightful interpretation involving studying a corpus of text representing a discourse; weighing socio-cultural contexts of statements; exploring intertextual relationships within and between texts that constitute interfaces between discourses and institutional contexts; and exploring connections and themes that are saliently absent from texts (Fairclough, 1995; Gee, 2005). As theoretically rich and interpretive analysis, discourse analysis requires particular attention to demonstrating that researchers’ interpretations are substantiated by the data; therefore, warranting for knowledge is particularly critical in discourse analysis (Wood & Kroger, 2000). Because results stem from complex interpretative processes, an appropriate combination of data and interpretation, which anchors interpretations in texts by linking derived interpretations to analyzed texts, is particularly important in providing evidence in discourse analysis (Wood & Kroger, 2000). The challenges of substantiating claims of process and results are exacerbated by the challenges of representing process and results, which we discuss next.

Representation of Analysis Process and Results

Another significant challenge is apt representation of analysis process and results in ways that are accessible as well as interpretable by readers, and are sufficiently efficient to comply with expectations of publication outlets (Alvermann, O’Brien, & Dillon, 1996; Anfara et al., 2002; N. Phillips et al., 2008). This challenge is related to the challenges of transparency and warranting claims because “We can know a thing only through its representations” (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000, p. 5). Representation refers to the choices involved in presenting what has been gained or learned from a study and how it has been learned, thereby transforming researchers’ cognitions into public form so they can be shared with others and inspected (Eisner, 1981, 1993).

The challenge of representation is twofold. First, representation requires researchers to find ways to present the process of data analysis in textual and/or visual form in order to publicly disclose the research process and to demonstrate the rigor of the analysis (Anfara et al., 2002; Harry et al., 2005). A common challenge in qualitative research is how to represent nonlinear (e.g., iterative, circular) analysis processes in a research report (Bringer, Johnston, & Brackenridge, 2004). Researchers may be challenged to find alternative forms of representation in order to map these processes; even visual representations, as alternatives to text, are likely to vastly simplify actual processes by which researchers arrive at interpretations and may nourish illusions of linearity of the processes (Harry et al., 2005). This challenge is more prevalent in representing an iterative and highly interpretive process, such as discourse analysis.

Second, qualitative researchers need to find ways to represent their results, including presentation of data evidence and its interpretation to support knowledge claims. As indicated above, representation of evidence for individual results (drawn from the entire data set) can be challenging because in discourse analysis researchers interpret and draw inferences regarding the meanings constructed through discourses represented in texts, and the representation of results has to provide both evidence from data and evidence for the appropriateness of inferences drawn. Hence, researchers need to find a balance between representing data to establish the credibility of results and inferences, and representing their interpretations for their readers (Pratt, 2008; Wolcott, 2001). Creative forms of representation may be necessary to accomplish this task and to portray the chain of evidence in discourse analysis, while at the same time conforming to expectations of journals.

Recommendations to Address These Challenges in Discourse Analysis

In sum, discourse analysts face the challenges of performing systematic and rigorous analyses to capture a discourse’s functions, of reporting discourse analyses transparently, of providing appropriate evidence to warrant claims, and of representing their analyses and results. We now introduce several tools designed to address these challenges and potentially enhance the trustworthiness of discourse analytic studies; each of these tools addresses one or more of the four challenges we identified. While the challenges are conceptually distinct, in empirical studies they are intertwined and need to be resolved accordingly; hence, although we do not suggest that all these tools have to be used in a single study, in the following we demonstrate how the recommended tools address these challenges collectively.

Background of Empirical Example

To illustrate these tools, we use examples from a discourse analysis of strategic management discourse in public education we have conducted. Although presenting our full analysis is beyond this article’s purposes, we briefly provide its background and rationale. Motivated by the observation that ever more problems are considered suitable for the application of strategic management (Greckhamer, 2010; Levy, Alvesson, & Willmott, 2003; N. Phillips & Dar, 2009; Whipp, 1999), in our study, we explored the discursive construction of strategic management for the public school sector. Whereas strategic management is naturalized as a/the solution to the problems of managing public sector organizations, our objective was to denaturalize the expansion of the strategic management discourse into the domain of public education administration to understand the functions and sources of strategic management’s promotion in this domain. The purpose of the project from which we draw here was to shed light on the discursive functions produced by the selected discourse, in order to understand the reality constructed or redefined by this discourse, the ends this reality serves, and how this reality is naturalized by the discourse (and consequently to denaturalize it). Its theoretical relevance and empirical contribution lies in increasing our understanding of the expansion of strategic management discourse into the realm of public education administration; this, in turn, enhances our understanding of managerialist reforms in education, and contributes to critical approaches to school administration research.

Consistent with the study’s purpose, we selected a specific discourse produced by Harvard University’s Public Education and Leadership Project (PELP). PELP is a key center reshaping American public education by producing and applying discourses of strategy to the organization and management of public school districts; it has a powerful and far reaching influence through its partnership with 15 North American school districts representing more than 1 million students (Harvard, n.d.), and its alumni and other affiliates hold key leadership positions in some of the US’s largest school districts. The texts produced by PELP are integral for its training activities directed at U.S. school district leaders; since its inception a decade ago, PELP has developed a library of teaching and case notes encompassing more than 50 items (Harvard, 2013). We analyzed three texts produced by PELP as the corpus of data (Childress, Elmore, & Grossman, 2005, 2006; Childress, Elmore, Grossman, & King, 2007) because they represent the project of this center to develop “a knowledge base for the strategic management of public education” (Childress et al., 2005, p. 6), as well as the theoretical framework underpinning PELP’s teaching materials.

A Framework for Systematic Analysis of Discourse Building Blocks

Turning to the tools to address the aforementioned challenges, we recommend five tools and illustrate their use through examples from our empirical study. Starting from the premise that discourse analysis aims to explore how a discourse is organized to accomplish its various purposes (Wood & Kroger, 2000), the first recommended analytical tool is a framework enabling systematic analysis of discourse building blocks. Discourses constitute the building blocks of social systems (Clegg, Courpasson, & Phillips, 2006) by simultaneously constituting social identities, social actions and relations, social institutions, and systems of knowledge and belief (Fairclough, 1993; Luke, 1996). Because each discourse builds social reality in a particular way, overly structured and mechanical approaches of analysis would not be suitable. Nonetheless, a framework for systematic analysis can capture these elements of social realities and functions of discourse while allowing for the emergent aspects of data analysis and for researchers’ interpretations based on their individual values and interests.

A framework developed by Gee (2005, 2011) enables systematic analyses of core discourse building blocks. Without constituting a mechanical template that would impede researchers’ interpretations and application of theoretical knowledge to analyzing how discourses produce these building blocks and their meanings, it provides structure and guidance to investigate how a view of reality is constructed through discourse, including a broad set of analytical questions (see Gee, 2005, pp. 110–113) directed at illuminating a discourse’s major functions. Synthesizing the discourse analysis literature, Gee (2005, 2011) identified seven interrelated aspects of reality that we always and simultaneously construct through discourse— namely, significance, activities, identities, relationships, politics, connections, and sign systems and knowledge. Below we describe these building blocks and their domains of analysis (of discourse functions). In-depth examples of analyzing specific building blocks of discourse are provided throughout our discussion of tools (specifically under tools of chronicling the analysis process, narrating the interpretive process, and crafting a description of results).

First, analysis of significance building examines how meanings and significances of certain things, occurrences, institutions, objects, and problems—including their (un)importance or (ir)relevance—are (re)produced, transformed, and/or integrated through discourse. Second, analysis of activity building focuses on how discourses build certain kinds of activities that are being recognized in a social environment, involving main activities and sub-activities composing them. Third, analysis of identity building captures how situated meanings of identities in a discourse are accomplished, including what types of identities are relevant, taken for granted, or under construction. Fourth, analysis of relationship building focuses on how a discourse builds, sustains, takes for granted, transforms, and/or deteriorates the relevance and/or importance of relationships among individuals, groups, institutions, discourses, and/or texts. Fifth, analysis of political building involves analyzing how sources of individuals’, groups’, or institutions’ power, status, legitimacy, and worth are built or destroyed, for example, by sustaining (or undermining) connections to entities or concepts that are considered to be normal, important, and/or respected. Sixth, analysis of connection building explores how aspects of reality, such as individuals, themes, institutions, texts, past, present, future, and also discourses are portrayed as connected and relevant (or disconnected and irrelevant) to each other, as well as what connections are taken for granted, transformed, and/or missing. Seventh, analysis of building sign systems and knowledge focuses on how a discourse operates, values, or disvalues certain sign systems (e.g., different forms of written or spoken language) and forms of knowing, thereby making relevant and privileging (or making irrelevant and disprivileging) certain types of knowledge, or how it uses intertextuality to allude to other forms of knowledge.

Below we provide examples of how we have applied Gee’s framework to analyze our focal discourse. We also note that the discourse building blocks are interrelated and together construct reality. Hence, analyses focusing on specific discourse building blocks would benefit from giving at least some consideration to all these interrelated functions of discourse (Gee, 2005). We recommend Gee’s framework as a suitable device to address some of the identified challenges because of its comprehensiveness, however other frameworks that are similarly systematic and explicable may equally well fulfill the purposes of addressing the related challenges of discourse analysis.

Chronicling the Discourse Analysis Process

To demonstrate and enable evaluation of rigor in qualitative research, researchers should provide a chain of evidence to explicate how they moved from data to results (Constas, 1992). This is the case because concepts do not emerge from the data; they are created and imbued with meaning by researchers based on particular analytical processes and decisions (Anfara et al., 2002; Constas, 1992), which in turn should be transparently portrayed and communicated so as to provide proper evidence to readers evaluating the analysis. To accomplish these goals in discourse analysis, we suggest the use of a tool we call chronicling, which describes the major analysis processes utilized and macro-level decisions made in analyzing and interpreting data. As any representation, this tool remains a simplification of the complexity of the analysis process (Anfara et al., 2002).

Here, we illustrate the use of chronicling by presenting an example from our study. We began by conferring on Gee’s (2005, 2011) discourse analysis framework. Then, in multiple cycles of independent analyses, each of us identified theoretically relevant data units and interpreted them in their context, identified instances of Gee’s building blocks, and documented relationships between data units and building blocks, resulting in the first draft of our concepts. Our analysis was theoretically guided by Gee’s general framework of discourse building blocks, the diagnostic questions he recommended asking about the discourse’s building tasks (these helped us to refrain from letting themes purely be driven by the data without fitting data into a predetermined coding scheme), and our research questions and purposes; it involved searching for potential connections between data units and building blocks. We refer to such connections between data units and discourse building blocks as concepts (Ryan & Bernard, 2003). For example, we analyzed the data for elements of discourse that privileged (disprivileged) certain ways of knowing or believing as well as claims to knowledge and beliefs as instances of building sign systems and knowledge. We originated tentative descriptive labels for developed concepts and categorized other relevant data units under them. Consequently each of us conducted two more cycles of independent analysis verifying or refining (combining, splitting, changing, and adding to) his or her set of concepts, while making extensive annotations to anchor specific observations and questions. These analysis cycles resulted in two independent sets of outcomes including theoretically relevant data units and sets of concepts. Each concept consisted of a brief mnemonic (for organization purposes), a definition as well as a detailed explanation of its logic, and criteria for relating data to the concept (MacQueen, McLellan-Lemal, Bartholow, & Milstein, 2008). We also noted data units fulfilling important discourse functions but that we could not readily connect to any building block, marking them for further analysis.

As recommended (MacQueen et al., 2008), one of us (i.e., the first author) took primary responsibility for maintaining a master list of concepts, and this person combined our independent analyses, combining substantively similar concepts (on the basis of descriptions, included data units, allocation to building blocks, annotations, and memos), and evaluating the consistency of data units with the concepts’ overall descriptions and labels, while also documenting discrepancies in independent analyses. For example, some concepts were inconsistent between two analyses or were too broad and vague, while other concepts partially overlapped with each other. The second author reviewed this combined analysis, provided recommendations on how to resolve documented issues, and noted additional issues. We then further discussed each concept regarding whether it captured an important element of the discourse’s building blocks, until we agreed on all concepts, the data units representing them, their connections to building blocks, and agreed that the concepts were reasonably “exhaustive and mutually exclusive” (Constas, 1992, p. 260).

Our independent analyses and common decisions were vital because the analyzed discourse was interdisciplinary and spanned our respective fields of expertise (management and education). In general, agreement on the evaluation of functions of discourse elements among two or more analysts is important for enhancing discourse analyses’ rigor (Gee, 2005). While it may be costly in terms of time (and perhaps other resources), this is particularly advisable when analyzing archival data rules out opportunities for member checks and similar tools.

In sum, chronicling the multi-cycle processes of individual analyses, as well as discussions and conferrals in identifying discourse building blocks, enhances a study’s transparency and provides evidence of rigor. Although we had to significantly summarize our analysis processes due to space constraints (a common challenge faced by researchers writing up discourse analyses for journal publication consideration), chronicling both enabled us to provide evidence of rigor and it guided us to be cognizant of the analysis process. In addition, our use of NVIVO software for analysis was helpful in this process of chronicling; it facilitated recording, editing, and sharing consecutive analyses stages, thereby enabling us to keep organized records of (and later report) all analysis steps and decisions in addition to our results. However, this and similar software are merely tools supporting the kind of analysis researchers want to apply; the actual analyses and decisions are performed by the researchers (Fielding, 2010; Saldaña, 2009), based on theoretical commitments and analytical thought processes.

Tabulating the Discourse Analysis Process

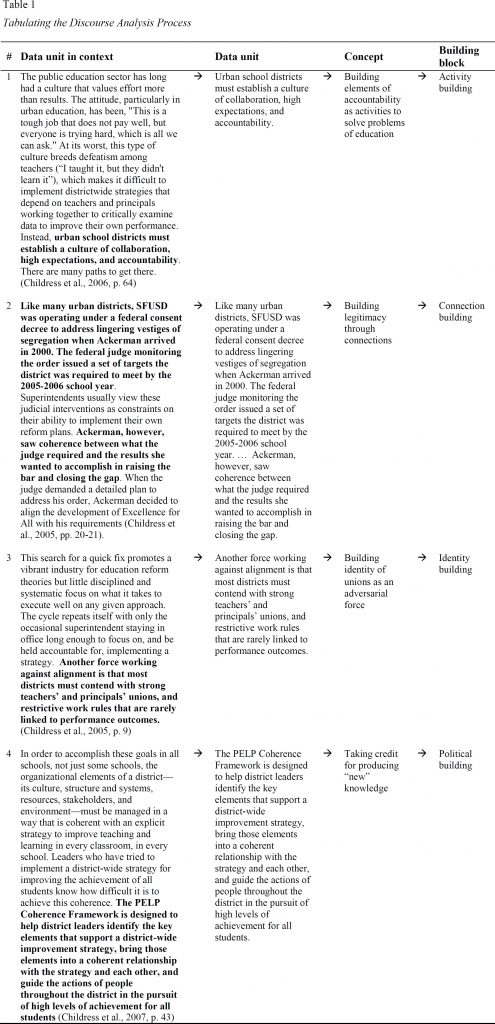

Tufte (2006) noted that data and the final published research report are typically separated by “the shadow of the evidence reduction, construction, and representation process: data are selected, sorted, edited, summarized, massaged, and arranged into published graphs, diagrams, images, charts, tables, numbers, words” (p. 147). Owing to its interpretative nature, discourse analyses may be challenged on the basis of how conclusions were reached based on specific data. As one way to cope with these challenges, we suggest tabulating the discourse analysis process to represent the process of analysis and interpretation by providing anchors connecting data units, specific points of reasoning (i.e., concepts), and building blocks. This tool addresses three challenges. First, it illustrates intermediary data analysis steps and the discourse analysts’ line of reasoning, which increase a study’s transparency. Second, it includes data samples connected to results, thereby providing evidence of original data in context of the larger text. Finally, it enables a relatively concise visual representation of complex and non-linear analysis processes. We illustrate this tool’s use with an example from our study (See Table 1).

In Table 1, the column Data unit in context presents a segment of raw data, with the data unit in bold. This facilitates transparency by showing additional textual context of a data unit that informed our identification and interpretation of data units. The next column shows Data units, that is, textual elements we identified as contributing to construct one of the discourse’s functions and thereby building blocks. Together, these two columns provide evidence of data that contributed to our conclusions. The third column shows the Concept represented by a data unit, which captures this (and other related) data unit’s contribution to a specific function of the discourse and consequently to a building block. The fourth and last column shows the building block this concept serves to construct. This tabular format represents the analysis process because by showing important anchors (i.e., data unit in context, data unit, concept, and Building block), each row summarizes our line of reasoning to reach conclusions. To give an example, in our analysis we identified a concept building legitimacy through connections that captures the discourse’s function of making connections to legitimate ideas and/or people to increase its own legitimacy; the particular data unit in row 2 of Table 1 is an instance of building a connection to a vital social justice (and legal) issue (i.e., referring to overcoming segregation of schools to build the discourse’s legitimacy). In our study, each building block was represented by multiple concepts, and each concept was represented by multiple data units. In addition, some statements may constitute a data unit for multiple concepts and building blocks, because any given element of discourse may fulfill multiple functions in constructing reality (see example below) as building blocks co-construct reality.

In discourse analysis, effective presentation of process requires showing how claims and interpretations are substantiated by analysis and data (Wood & Kroger, 2000), because selected data units are not assumed to speak for themselves. Tabulating the analysis process by linking raw data to data units, concepts, and building blocks, Table 1 offers a glimpse of analyses and interpretation processes rather than merely showing data; the table also helps researchers to illustrate the chain of evidence in complex analyses. Each row in the table is informed by both theory and data and represents an increment of the analysis and of our reasoning to reach conclusions. However, as described above, the table should not be read as representing a linear process of moving from data to concepts and building blocks; like any representation, it is a simplification of the analysis process, including only its pivotal parts. Finally, the number of rows to show in this table may depend on analysis and targeted outlets, although the aim should be to show enough to convey the logic of interpretation and analysis processes.

Narrating the Process of Interpretation

In addition to tabulating the process as illustrated, another tool we refer to as narrating the process of interpretation, serves to explicate the analysis through narrating the interpretative process moving from raw data to concepts and building blocks for specific data units, thereby complementing the process table and addressing the process-related challenges of discourse analysis. Such narration may include not only the final interpretation included in the results but also intermediary stages of interpretation (e.g., questions asked, discussions, or ruled out alternative interpretations); one or more narratives of interpretation can document the processes underlying researchers’ interpretations and decisions at critical junctures, thereby helping to address several challenges. First, by explaining the thought process and logic underlying analysts’ interpretations moving from raw data to results, process narratives enhance transparency and enable public scrutiny of the analysis. Second, narrating provides evidence of rigor by showing the depth of analysis not apparent in the final description of results. Third, narratives of interpretation are an alternative tool for representing the complex analysis process; in conjunction with tabulating the process, narrating interpretations can provide a relatively authentic representation of complex analysis processes.

Number and depth of narratives of interpretation appropriate to address these challenges depend on the specific study (e.g., its topic, level of interpretation, and publication target). Here we give an example from our study related to the concept building the knowledge and sign system of strategy. Representing the building block building sign systems and knowledge, this concept contributes to establishing relevant claims for different ways of knowing and believing. Constituting a small portion of the entire analysis, this narration serves as an exemplar helping to explicate our interpretative process. Consider these two illustrative data units:

Specifically, district offices must carry out what we call the strategic function—that is, they need to develop a districtwide strategy for improving teaching and learning and to create an organization that is coherent with the strategy. (Childress et al., 2006, p. 59)

Strategy is the set of actions a district deliberately takes to provide capacity and support to the instructional core with the objective of raising student performance district-wide. Strategy informs how the people, activities, and resources of a district work together to accomplish a collective purpose. (Childress et al., 2007, p. 45)

The first author associated the first data unit with capturing the application of strategy to educational institutions. Considering the data unit in context, this author annotated that the discourse moved the focus from teaching and learning in classrooms, to strategy making in school district offices. Similarly, he also interpreted the second data unit as having the function of applying strategy knowledge to educational institutions, further noting that this data unit constructed the relevance of the system of knowledge of strategy to educational institutions by providing a tailored definition of strategy for the context of teaching and learning in schools, and by defining raising student performance as a key outcome of strategy for educational institutions.

These and other data units led the first author to develop a tentative concept capturing the function making strategy relevant for educational organizations and school districts. This author further inferred that within Gee’s framework this function evoked the questions “what systems of knowledge and belief are made relevant (or irrelevant)” in the discourse, and “how are they made relevant (and irrelevant), and in what ways” (Gee, 2005, p. 112), and he concluded that this concept’s function was a manifestation of the building block building sign systems and knowledge. The second author had tentatively developed a concept reinventing the wheel, which captured a function of constructing “new” knowledge by repackaging traditional functions of school districts as new knowledge. She also noted that the purpose of these data units was building significance of a system of knowledge, with the emphasis on constructing the novelty of this knowledge. The second author also associated this discourse function with the building block building sign systems and knowledge. Upon agreeing that the function of these data units was an instance of this particular building block, we discussed the interpretations we had linked to our respective concepts. We concluded that strategy for educational institutions was presented as new knowledge system, which was made relevant for education by referring to familiar functions of school districts; consequently we converged on a refined concept building the significance of strategy knowledge for educational organizations (used in further rounds of analysis). Our insights from discussing the tentative concept reinventing the wheel also informed another concept we formed, taking credit for producing new knowledge belonging to the political building block (see row 4 in Table 1).

We note that in our overall analysis we associated some data units with multiple discourse functions; for example, according to our joint analysis, data unit 1 above had three different functions and thus was connected to three different concepts and building blocks: In addition to the first function just discussed, its second function was activity building by contributing to constructing strategy as a solution for resolving constructed problems, captured by our concept building the activity of strategy making as solution to problems constructed by the discourse. Its third function, captured by a concept building the identity of the district office, was to contribute to identity building by constructing the district office’s identity and ascribing to it the jurisdiction of carrying out the strategic function. We had very close interpretations regarding these functions as well as concept description and labels, and thus reached an agreement on the final interpretation.

Crafting the Description of Findings

In addition to the tools we have proposed so far, crafting a description of the study’s findings is an essential part of any discourse analysis. Already present in some form in virtually every empirical discourse analysis, a key tool is laying out a study’s conclusions instantiated by prototypical quotes from the data (Bernard & Ryan, 2010). We believe this tool should be used in conjunction with those presented above and we illustrate a description that addresses some of the challenges of discourse analysis. An effective presentation of findings should include a clear link to data, not only providing examples of data units, but also interpreting how these data units become the basis for these findings in order to address the challenges of providing data as evidence of knowledge claims. In crafting a description of results, inclusion of data should not serve merely as an embellishment of or to give flavor to the description; the specific elements of data chosen as evidence—as well as proper description of the context—should serve as anchors for the researchers’ interpretations. This presentation should build on the literature as needed to describe the interpretations.

Moreover, discourse analysts should consider two aspects in deciding what data evidence to represent. First, because only a small portion of data evidence can be included, along with other forms of evidence, researchers may find it useful to identify and weave into their interpretations data units that constitute evidence for the study’s findings and at the same time are particularly poetic, concise, or insightful, and thus compelling (see Pratt, 2008). Also, the amount of sufficient evidence depends on the research context; showing how individual results and overall claims are supported by data does not call for a certain number of data unit samples (Wood & Kroger, 2000). Second, proper balance of showing and interpreting data in qualitative inquiry (Pratt, 2008; Wolcott, 2001) is particularly important for discourse analysis; because it is not assumed that language is transparent or that data speak for themselves, it is essential to communicate authors’ interpretations. In sum, crafting a description of results that balances showing data and interpreting it helps address two challenges of discourse analysis: providing evidence of data and representing that evidence effectively.

Within the space constraints of this article, we briefly illustrate this tool by providing two excerpts from our results, related to our concept omitting connections to support other functions of discourse. This concept captures the functions of discourse elements that leave out certain connections that would be considered natural, obvious, plausible, and/or rational. It is part of the connection building block, which portrays (stabilizes and transforms) aspects of the world as connected (or disconnected) to each other. These omissions (captured by our concept) constitute important functions of the discourse, and identifying connections that are missing may be vital in understanding and denaturalizing a discourse’s functions (Fairclough, 1995; Gee, 2005). Consider data unit 3 below illustrating this concept:

Only about 70% of U.S. students graduate from high school, which puts the United States tenth among the 30 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and behind such countries as South Korea and the Czech Republic. On a mathematics test given to 15-year-olds in OECD countries, American students placed 24th out of 30. (Childress et al., 2006, p. 56)

This data unit constructs the argument that students in the United States are performing poorly in comparison to students in other (including relatively newly) industrialized nations. From the point of view of both strategic management and educational policy, an appropriate inference from the presented statistics would be to call for close comparisons of the U.S. education system with higher performing ones in order to identify and potentially adopt key elements and policies of these more successful systems; benchmarking to identify and potentially imitate the strengths of successful organizations is a key notion in strategic management (Porter, 1985) as is the cross-national borrowing of successful educational policies and practices in comparative education (Steiner-Khamsi, 2004). Omitting this connection protected the coherence of the discourse’s claims that PELP needed to build and use new knowledge (i.e., a framework for strategic management of public schools) as the ultimate solution to improve the performance of U.S. schools, ironically requiring an omission of obvious connections to strategy knowledge. Consider the following data unit for further evidence of the omission of connections to serve the discourse’s functions.

When school boards hire the next superintendent, it is rarely to continue and deepen a predecessor’s approach, but rather to introduce the newest set of reform ideas and the next strategy for change. Not surprisingly, this churn contributes to a leadership team’s focusing on the short-term, which results in a lack of clarity about the strategic direction of a district. During our interviews we hardly found a senior manager, much less a principal or teacher, who could articulate her district’s strategy for improved student performance. (Childress et al., 2005, pp. 8–9)

This second example is intended to support the discourse’s broader argument that educational organizations should adopt strategy knowledge (adapted from the realm of business) because an absence of strategic thinking inadvertently fosters dysfunctional processes and an emphasis on the short term as opposed to a district’s strategy (hence leaders are not able to formulate this strategy). However, the viability of both branches of this argument relies on a missing connection. First, the strategy literature has identified potential short-term orientation as a key pervasive problem among corporate managers, particularly in the U.S. (Laverty, 1996). Similarly, previous research suggests that corporate executives, when asked, are frequently not able to articulate the strategy of their firms (Whittington, 2001). Thus, pointing out what educational organizations do wrong without pointing to analogous flaws in the corporate world helps to sustain the (lopsided) argument that imitating practices from the world of corporate management would solve problems of public education. Making these connections would impair naturalizing the reality under construction that strategic management (taught in business schools and practiced in business organizations) can resolve the problems of educational institutions.

Conclusion

A key issue for qualitative researchers is convincing their audience of the quality, integrity, and import of their research (Golden-Biddle & Locke, 1993). In this respect, researchers conducting discourse analysis, as with other forms of qualitative research, face key challenges that they should address while adhering to theoretical premises and foundations of discourse analysis. In this article, we have identified and discussed four major challenges for qualitative research in the context of discourse analysis; these challenges, although conceptually distinct, occur and therefore need to be resolved in an interdependent fashion when conducting a discourse analysis. We have suggested five tools that contribute to addressing these challenges. Although these tools can be used selectively as appropriate to the specific research context to address the challenges while at the same time complying with journals’ format and length requirements (N. Phillips et al., 2008; Pratt, 2008), they are complementary and therefore are highly effective in addressing the challenges to discourse analysis focused on in this article when they are used in conjunction.

We share the perspective that it would be inappropriate to reduce the practice of qualitative research, which includes interpretive, intuitive, and artistic processes, to technical issues that can be resolved by “cookbook methods” (Anfara et al., 2002, p. 34) and we agree that in presenting qualitative research “one narrative size does not fit all” (Tierney, 1995, p. 389). Nevertheless, we believe it is important for qualitative researchers to be forthcoming about how they analyze and interpret their data in order to enhance the trustworthiness of their study, their interpretive acts, and their findings (Peshkin, 2000). In this article we have provided an array of key challenges for discourse analysis and specific recommendations for addressing them using examples from an empirical study; we thereby facilitate more systematic, rigorous discourse analysis studies that are transparent, more successfully warrant their claims through evidence, and represent their results in ways that support transparency and substantiation of claims, while at the same time remaining true to their epistemological and theoretical commitments. We primarily intend our article to serve as a resource for researchers involved in conducting and writing up empirical discourse analytic studies by both explicitly laying out some of the major challenges they are likely to face and providing recommendations for how they could address these challenges; we hope that this discussion contributes to helping researchers overcome these challenges in their research and that it thereby contributes to and facilitates increased recognition of discourse analysis in various domains of qualitative inquiry. In addition, we believe our discussion of key challenges of qualitative research, and our suggestions for addressing these challenges in the context of empirical discourse analyses, can inform discussions of and serve as a model for addressing the challenges faced in the context of other qualitative methodologies and thus contribute to the advancement of qualitative research more generally.

References

American Educational Research Association [AERA]. (2006). Standards for reporting on empirical social science research in AERA publications. Educational Researcher, 35(6), 33–40. Crossref.

American Educational Research Association [AERA]. (2009). Standards for reporting on humanities-oriented research in AERA publications. Educational Researcher, 38(6), 481–486. Crossref.

Alvermann D. E., O’Brien D. G., & Dillon D. R. (1996). On writing qualitative research. Reading Research Quarterly, 31(1), 114–120. Crossref.

Alvesson M., & Kärreman D. (2001). Varieties of discourse: On the study of organizations through discourse analysis.

Human Relations, 53(9), 1125–1149. Crossref.

Anfara V. A., Brown K. M., & Mangione T. L. (2002). Qualitative analysis on stage: Making the research process more public. Educational Researcher, 31(7), 28–38. Crossref.

Bernard H. R. (1994). Research methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Bernard H. R., & Ryan G. (2010). Analyzing qualitative data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Bringer J. D., Johnston L. H., & Brackenridge C. H. (2004). Maximizing transparency in a doctoral thesis: The complexities of writing about the use of QSR*NVIVO within a grounded theory study. Qualitative Research, 4(2), 247–265. Crossref.

Bryman A., Becker S., & Sempik J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(4), 261–276. Crossref.

Burrell G., & Morgan G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis. London, England: Heinemann.

Chalaby J. K. (1996). Beyond the prison-house of language: Discourse as a sociological concept. British Journal of Sociology, 47(4), 684–698. Crossref.

Chia R. (2000). Discourse analysis as organizational analysis. Organization, 7(3), 513–518. Crossref.

Childress S., Elmore R., & Grossman A. (2005). Promoting a management revolution in public education (HBS Working Paper Number 06-004). Harvard Business School, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.

Childress S., Elmore R., & Grossman A. (2006, November). How to manage urban school districts. Harvard Business Review, 84, 55–68.

Childress S., Elmore R., Grossman A., & King C. (2007). Note on the PELP coherence framework. In Childress S., Elmore R., Grossman A., & Johnson S. M. (Eds.), Managing school districts for high performance: Cases in public education leadership (pp. 43–54). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Clegg S., Courpasson D., & Phillips N. (2006). Power and organizations. London, England: Sage Publications.

Constas M. A. (1992). Qualitative analysis as a public event: The documentation of category development procedures.

American Educational Research Journal, 29(2), 253–266. Crossref.

Crotty M. (1998). The foundations of social research. London, England: Sage Publications.

Davies D., & Dodd J. (2002). Qualitative research and the question of rigor. Qualitative Health Research, 12(2), 279– 289. Crossref. PubMed.

Denzin N. (2009). The elephant in the living room: Or extending the conversation about the politics of evidence. Qualitative Research, 9(2), 139–160. Crossref.

Denzin N., & Lincoln Y. (2000). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In Denzin N. & Lincoln Y. (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Eisner E. (1981). On the differences between scientific and artistic approaches to qualitative research. Educational Researcher, 10(5), 5–9. Crossref.

Eisner E. (1993). Forms of understanding and the future of educational research. Educational Researcher, 22(7), 5–11. Crossref.

Elizabeth T., Anderson T. L. R., Snow E., & Selman R. L. (2012). Academic discussions: An analysis of instructional discourse and an argument for an integrative assessment framework. American Educational Research Journal, 49(6), 1214–1250. Crossref.

Fairclough N. (1985). Critical and descriptive goals in discourse analysis. Journal of Pragmatics, 9, 739–763. Crossref.

Fairclough N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Fairclough N. (1993). Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: The universities. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 133–168. Crossref.

Fairclough N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. London, England: Longman.

Fairclough N. (2003). Analyzing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. London, England: Routledge. Crossref.

Fielding N. (2010). Elephants, gold standards and applied qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 10(1), 123–127. Crossref.

Fisher B. A. (1977). Evidence varies with theoretical perspective. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 41(1), 9–19. Crossref.

Foucault M. (1972). The archeology of knowledge (Sheridan Smith A. M., Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Foucault M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York, NY: Vintage.

Foucault M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977 (Gordon C., Marshall L., Mepham J., & Soper K. (Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Fournier V., & Grey C. (2000). At the critical moment: Conditions and prospects for critical management studies. Human Relations, 53(1), 7–32. Crossref.

Freeman M., deMarrais K., Preissle J., Roulston K., & St. Pierre E. A. (2007). Standards of evidence in qualitative research: An incitement to discourse. Educational Researcher, 36(1), 25–32. Crossref.

Gee J. (2005). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gee J. (2011). How to do discourse analysis: A toolkit. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gee J., & Greene J. (1998). Discourse analysis, learning, and social practice: A methodological study. Review of Research in Education, 23, 119–169. Crossref.

Gee J., Hull G., & Lankshear C. (1996). The new work order: Behind the language of the new capitalism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Golden-Biddle K., & Locke K. (1993). Appealing work: An investigation of how ethnographic texts convince.

Organization Science, 4(4), 595–616. Crossref.

Grant D., & Hardy C. (2003). Introduction: Struggles with organizational discourse. Organization Studies, 25(1), 5–13. Crossref.

Grant D., Hardy C., Oswick C., & Putnam L. (Eds.). (2004). The Sage Handbook of Organizational Discourse. London, England: Sage Publications.

Greckhamer T. (2010). The stretch of strategic management discourse: A critical analysis. Organization Studies, 31, 841–871. Crossref.

Guba E. (Ed.). (1990). The paradigm dialog. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Hammersley M. (1997). On the foundations of critical discourse analysis. Language & Communication, 17(3), 237–248. Crossref.

Hammersley M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 30(3), 287–305. Crossref.

Harding S. (1987). The method question. Hypatia, 2(3), 19–35. Crossref.

Harding S. (1996). Gendered ways of knowing and the “epistemological crisis” of the West. In Goldberger N. R., Tarule J. M., Clinchy B. M., & Belenky M. F. (Eds.), Knowledge, difference, and power: Essays inspired by women’s ways of knowing. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Hardy C. (2001). Researching organizational discourse. International Journal of Management & Organization, 31(3), 25–47. Crossref.

Hardy C., & Phillips N. (2004). Discourse and power. In Grant D., Hardy C., Oswick C., & Putnam L. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational discourse. London, Sage: Sage Publications. Crossref.

Harry B., Sturges K. M., & Klinger J. K. (2005). Mapping the process: An exemplar of process and challenge in grounded theory analysis. Educational Researcher, 34(2), 3–16. Crossref.

Harvard University. (2013). Public education leadership project: Extending and expanding the impact into the second decade. Retrieved from http://projects.iq.harvard.edu/files/hbstest/files/pelp_strategy_building_summary_revised.pdf

Harvard. (n.d.). Public education leadership project at Harvard University. School districts. Retrieved from http://www.hbs.edu/pelp/school.html

Howe K., & Eisenhart M. (1990). Standards for qualitative (and quantitative) research: A prolegomenon. Educational Researcher, 19(4), 2–9. Crossref.

Jaworski A., & Coupland N. (Eds.). (2006a). The discourse reader (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Jaworski A., & Coupland N. (2006b). Introduction: Perspectives on discourse analysis. In Jaworski A. & Coupland N.

(Eds.), The discourse reader (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Johnstone B. (2002). Discourse analysis. Maiden, MA: Blackwell.

King G., Keohane R. O., & Verba S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kress G. (1990). Critical discourse analysis. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 11, 84–99. Crossref.

Lamont M., & White P. (Eds.). (2005). Workshop on interdisciplinary standards for systematic qualitative research. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation.

Laverty K. J. (1996). “Short-termism”: The debate, the unresolved issues, and the implications for management practice and research. Academy of Management Review, 21(3), 825–860.

Levy D., Alvesson M., & Willmott H. (2003). Critical approaches to strategic management. In Alvesson M. & Willmott H. (Eds.), Studying management critically (2nd ed., pp. 92–110). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Crossref.

Lincoln Y. (1995). Emerging criteria for quality in qualitative and interpretive research. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(3), 275– 289. Crossref.

Lincoln Y. (2002). On the nature of qualitative evidence. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Sacramento, CA.

Lincoln Y., & Guba E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newberry Park, CA: Sage Publications. Crossref.

Lincoln Y., & Guba E. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. In Williams D. (Es.), Naturalistic evaluation: New directions in program evaluation (Vol. 30, pp. 73–84). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Crossref.

Luke A. (1996). Text and discourse in education: An introduction to critical discourse analysis. Review of Research in Education, 21, 3–48.

Macbeth D. (2003). Hugh Mehan’s learning lessons reconsidered: On the differences between the naturalistic and critical analysis of classroom discourse. American Educational Research Journal, 40(1), 239–280. Crossref.

MacQueen K., McLellan-Lemal E., Bartholow K., & Milstein B. (2008). Team-based codebook development: Structure, process, and agreement. In Guest G. & MacQueen K. (Eds.), Handbook for team-based qualitative research (pp. 119–135). Lanham, MD: Altamira.

Morse J., Barrett M., Mayan M., Olson K., & Spiers J. (2002). Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 13–22. Crossref.

Peshkin A. (2000). The nature of interpretation in qualitative research. Educational Researcher, 29(5), 5–9. Crossref.

Phillips D. (1987). Validity in qualitative research: Why the worry about warrant will not wane. Education and Urban Society, 20(1), 9–24. Crossref.

Phillips N., & Dar S. (2009). Strategy. In Alvesson M., Bridgman T., & Willmott H. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of critical management studies (pp. 414–432). Oxford, Unitied Kingdom: Oxford University Press. Crossref.

Phillips N., & Hardy C. (2002). Discourse analysis: Investigating processes of social construction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Crossref.

Phillips N., Lawrence T., & Hardy C. (2004). Discourse and institutions. Academy of Management Review, 29(4), 635– 652. Crossref.

Phillips N., Sewell G., & Jaynes S. (2008). Applying critical discourse analysis in strategic management research.

Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 770–789. Crossref.

Porter M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. New York, NY: Free Press.

Pratt M. G. (2008). Fitting oval pegs into round holes: Tensions in evaluating and publishing qualitative research in toptier North American journals. Organizational Research Methods, 11(3), 481–509. Crossref.

Ragin C., Nagel J., & White P. (2004). Workshop on scientific foundations of qualitative research. Arlingon, VA: National Science Foundation.

Rogers R. (Ed.). (2004). An introduction to critical discourse analysis in education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ryan G. (2004). What are standards of rigor for qualitative research? In Lamont M. & White P. (Eds.), Workshop on interdisciplinary standards for systematic qualitative research (pp. 28–35). Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation.

Ryan G., & Bernard H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. Crossref.

Saldaña J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Schiffrin D., Hamilton H., & Tannen D. (Eds.). (2001). The handbook of discourse analysis. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Steiner-Khamsi G. (Ed.). (2004). The global politics of educational borrowing and lending. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Tierney W. G. (1995). (Re)presentation and voice. Qualitative Inquiry, 1(4), (379–390). Crossref.

Tracy K., & Mirivel J. C. (2009). Discourse analysis: The practice and practical value of taping, transcribing, and analyzing talk. In Frey I. & Cissna K. (Eds.), Handbook of applied communication research (pp. 153–177). New York, NY: Routledge.

Tracy S. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. Crossref.

Tufte E. R. (2006). Beautiful evidence. Cheshire, CN: Graphics Press.

van Dijk T. (Ed.). (1985). Handbook of discourse analysis (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Academic Press. van Dijk T. (1993). Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 249–283. Crossref.

Whipp R. (1999). Creative deconstruction: Strategy and organizations. In Clegg S., Hardy C., & Nord W. (Eds.), Managing organizations: Current issues (pp. 11–25). London, England: Sage Publications. Crossref.

Whittington R. (2001). What is strategy – and does it matter? (2nd ed.). London, England: Thomson.

Wolcott H. F. (2001). Writing up qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Wood L., & Kroger R. O. (2000). Doing discourse analysis: Methods for studying action in talk and text. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Contact

Thomas Greckhamer, PhD Associate Professor, Rucks Department of Management, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA

Sebnem Cilesiz, PhDAssistant Professor, Department of Educational Foundations and Leadership, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, Louisiana, USA

Citation

Greckhamer, T., & Cilesiz, S. (2014). Rigor, Transparency, Evidence, and Representation in Discourse Analysis: Challenges and Recommendations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 422–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691401300123

Copyright License

- Title: “Rigor, Transparency, Evidence, and Representation in Discourse Analysis: Challenges and Recommendations”

- Authors: “Thomas Greckhamer and Sebnem Cilesiz”

- Source: “https://journals.sagepub.com/”

- License: “CC BY-NC-SA 4.0”